Catholic Doctrine and Devotion

The Holy Chalice

Condensed from El Santo Cáliz by Manuel Sanchez Navarrete.

The Evangelists St. Matthew (26: 26-28), St. Mark (14: 22-24) and St. Luke (22: 19-20), as well as St. Paul in his First Epistle to the Corinthians (11: 23-25), relate in a similar manner, and with almost the same words, that the Lord Jesus, being united with His disciples to the celebrate the Pasch, in the night in which He was betrayed, "...took bread, and blessed, and broke, and gave to His disciples, and said: Take ye and eat: This is My Body." And a little later, "And taking the chalice He gave thanks: and gave to them, saying: Drink ye all of this. For this is My Blood of the New Testament, which shall be shed for many, for the remission of sins." (Mt. 26: 26-28)

The Evangelists St. Matthew (26: 26-28), St. Mark (14: 22-24) and St. Luke (22: 19-20), as well as St. Paul in his First Epistle to the Corinthians (11: 23-25), relate in a similar manner, and with almost the same words, that the Lord Jesus, being united with His disciples to the celebrate the Pasch, in the night in which He was betrayed, "...took bread, and blessed, and broke, and gave to His disciples, and said: Take ye and eat: This is My Body." And a little later, "And taking the chalice He gave thanks: and gave to them, saying: Drink ye all of this. For this is My Blood of the New Testament, which shall be shed for many, for the remission of sins." (Mt. 26: 26-28)

Thus was instituted the sublime mystery of the Holy Eucharist, and at the same time that wine-cup was converted into the most precious relic of Christianity; into the divine Chalice, which, in a pilgrimage of love, tradition tells us has gone from the Cenacle of Jerusalem to Rome, from Rome to Huesca, and from Huesca to San Juan de la Peña; into the fabulous and mysterious Holy Grail, about which the most beautiful legends have been forged and the most fantastic deeds of heroes and champions which have inundated Christianity with the grandeur of their virtues and the example of their knightly valor; and into the Holy Chalice, which, with the seal and evidence of history, kings have longed to possess, and because it was so decreed by the will of the Lord, was delivered to the devotion and piety of the City of Valencia. For from the ostensorium of its Chapel in the Metropolitan Basilica, it offers itself to the whole world as a permanent testimony of the most august and sublime of mysteries—that of the Institution of the Holy Eucharist on the memorable evening of the first Holy Thursday.

Structure of the Sacred Vessel

The Holy Chalice of the Last Supper, a work notable from a religious as well as archeological point of view, is formed of three distinct parts corresponding to different epochs.

The upper cup, made of oriental agate, is semispherical—9.5 cm in diameter at the middle of the cup, 5.5 cm in depth in its interior, and 7 cm in height from its base to its lip. Both its interior and exterior are entirely smooth, without adornment, with the exception of a simple linear incision, cut all the way around, very regularly, at a slight distance from the lip. One can observe a small fracture, about half way up, which divides into two parts, each of them reaching to the lip. Both of these fractures were produced on the same occasion, and one can notice a miniscule peripheral portion missing between the ornamental line and the lip, which surely corresponds to the place on the cup which received the blow. This occurred on April 3, 1744, on Good Friday. It was the custom to use the Holy Chalice, during the Liturgy of Holy Thursday and Good Friday, to contain the Blessed Sacrament when it was reserved on the Altar of Repose. The Archdeacon and canon of the Cathedral, Don Vicente Frígola Brizuela, who was the celebrant in those Liturgies, in the presence of Archbishop Mayoral, was going to remove the Blessed Sacrament from the Holy Chalice, covered by a pall and veil, which was tied below the node with a ribbon. When he untied the ribbon, the cup slipped from his hands, fell, and broke in the manner we have just described. Immediately and carefully, after recovering the Blessed Sacrament, the fragments of the Chalice were gathered together and returned to the tabernacle of the Altar of Repose. Later they were placed in the Chapel of the Relics. The master silversmith Luis Vicent was advised, and he arrived on the afternoon of the same day together with his sons, Luis and Juan. They proceeded to reconstruct the Holy Chalice in the presence of several canons, and of the notary Juan Claver, who made a record of the entire event.

The foot, which is formed by an oval-shaped and inverted bowl, is of the same color and material as the cup, although very different and inferior to it, both in the quality of the work as well as that of the stone. The base measures 14.5 cm at its longest and 9.7 cm at its shortest. It is garnished with pure gold, within which are mounted 28 pearls, two rubies, and two emeralds of great value.

Finally the neck with its node is 7 cm in height, and serves to unite the cup with the foot. It is connected to two handles, garnished with the purest gold and supported by the gold settings of the foot, with its pearls and precious stones.

A meticulous study of this historical and exceptional relic was undertaken in 1960 by Professor Antonio Beltrán of the University of Zaragoza. Here are some of his conclusions:

—The cup can be dated to between the 4th century B.C. to the 1st century A.D. It is the product of an Egyptian, Syrian, or perhaps a Palestinian workshop, and therefore may very well "have been present on the table of the Last Supper" and "could be that which Jesus Christ made use of to drink, to consecrate, or both."

—The cup can be dated to between the 4th century B.C. to the 1st century A.D. It is the product of an Egyptian, Syrian, or perhaps a Palestinian workshop, and therefore may very well "have been present on the table of the Last Supper" and "could be that which Jesus Christ made use of to drink, to consecrate, or both."

—The foot is an Egyptian or Arabic bowl from the 10th or 11th century, and was connected to the cup around the 14th century, to emphasize its exceptional importance.

—The pearls and precious stones which ornament the foot are of a later date, and may have been added when the Holy Chalice was venerated at San Juan de la Peña.

What Tradition Tells Us

Theologians teach that public veneration given towards an ancient relic for centuries establishes a presumption in favor of its authenticity, of equal value as the best historical documents.

Now there is a tradition, constant and uninterrupted, confirmed from the earliest ages of the Church by a document of the first magnitude, The Canon of the Holy Mass, and kept in Rome with the positive approbation of the first Popes for two centuries, which affirms and sustains the authenticity of this great treasure. From Pope St. Sixtus II and the martyrdom of St. Laurence, this affirmation is made more secure and solemnly authorized, above all in the Kingdom of Aragón and especially in the bishoprics of Huesca and Jaca, until finally it reaches the level of the historical, with documentation already fully and formally guaranteed.

There are also other reasons to support the probative force of the traditional veneration of the Holy Chalice—such as the consideration that it would be temerarious to even suspect that such a precious relic could be lost, since this would have been inexplicable carelessness on the part of the "master of the house," spoken of in the Gospel (Mark 14: 14), who surely owned the Chalice, and in whose house the Last Supper was celebrated. It would also have been such on the part of the Apostles, when we see that they have preserved so many other relics of Our Lord, no more important than this, such as the Holy Crib kept in St. Mary Major; the Table of the Last Supper, venerated in St. John Lateran; the Dish upon which the Paschal lamb was served, preserved in Genoa; the Holy Shroud of Turin; the Crown of Thorns, the Sacred Lance and Nails of the Passion, and the very Sepulcher in Jerusalem.

But let us see what tradition tells us:

It tells us that the precious Chalice must have been owned by a person of high lineage, since its richness and elegance denote an artistic and material category superior to that of the crude vessels of wood or clay then in use by ordinary people. It is to be supposed further that, as it belonged to the owner of the Supper Room, who, as the Evangelists tell us, was a wealthy man, since he possessed a spacious dwelling and servants, he would have offered to the Master the best of his vessels, together with the other utensils necessary for the legal supper, which preceded the first Eucharistic Consecration.

After the death of Our Lord, it is logical to suppose that the Sacred Chalice came into the custody of the Blessed Virgin, and of St. John—the Beloved Disciple and guardian of Mary—who used it to celebrate the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass in the presence of Our Lady.

Siuri, Bishop of Córdoba, and Sales whom he cites, among other historians, believe that after the death of the Blessed Virgin, and the separation of the Apostles to preach the Gospel to all nations, such an important relic would have become the possession of St. Peter, chosen by Jesus as the visible head of the Church. He would have carried it with him to Rome, where, after he himself made use of it to celebrate the Holy Sacrifice, it continued to be in the possession of the next 23 Popes, Successors of St. Peter, who continuously consecrated and drank, from the Chalice of the Redeemer, His Most Precious Blood, and who, more often than not, shed their own, in testimony of their Faith and in the defense of the Gospel.

The precise words which immediately precede the Consecration of the Precious Blood, repeated for so many centuries in the whole world by an infinity of priests and heard and read by a multitude of the faithful—"Accipiens et HUNC praeclarum calicem in sanctas ac venerabiles manus suas..." ("Taking THIS excellent chalice into His holy and venerable hands...")—appear to be a clear allusion to the Chalice of the Last Supper used by the early Popes in their Masses; which words continued to be used in the Canon of the Mass.

The Holy Chalice had remained in Rome for two centuries when there came a period of great violence—beginning with the persecution of Valerian and Gallieno, which surpassed all previous persecutions. The Roman Empire was in a state of economic impotence, and the riches of the Christians, which the persecutors imagined to be fabulous, were considered to be a good remedy. The edict appeared in the year 257 and was repeated in 258. The henchmen of Valerian devoted themselves to the plunder of Christian alms, even to the point of raiding the Catacombs, which were protected by Roman law. Pope St. Sixtus II was incarcerated and condemned to death for refusing to turn over to the Emperor the objects of value owned by the Church. But he still had the means to order his faithful Deacon and Treasurer, St. Laurence, to distribute those goods immediately amongst the poor. The faithful Deacon did so, with the exception of the Holy Chalice (see image right, depicting St. Laurence receiving the Holy Chalice in a locked case and distributing alms), which, moved by a fervent and undoubtedly inspired desire to save it at all costs from the danger facing it in Rome, he sent, two days before his own martyrdom, to Huesca in Spain, the city of his birth, accompanied by a letter of remission, in which he ordered that it be entrusted to his parents, Orencio and Paciencia.

The Holy Chalice had remained in Rome for two centuries when there came a period of great violence—beginning with the persecution of Valerian and Gallieno, which surpassed all previous persecutions. The Roman Empire was in a state of economic impotence, and the riches of the Christians, which the persecutors imagined to be fabulous, were considered to be a good remedy. The edict appeared in the year 257 and was repeated in 258. The henchmen of Valerian devoted themselves to the plunder of Christian alms, even to the point of raiding the Catacombs, which were protected by Roman law. Pope St. Sixtus II was incarcerated and condemned to death for refusing to turn over to the Emperor the objects of value owned by the Church. But he still had the means to order his faithful Deacon and Treasurer, St. Laurence, to distribute those goods immediately amongst the poor. The faithful Deacon did so, with the exception of the Holy Chalice (see image right, depicting St. Laurence receiving the Holy Chalice in a locked case and distributing alms), which, moved by a fervent and undoubtedly inspired desire to save it at all costs from the danger facing it in Rome, he sent, two days before his own martyrdom, to Huesca in Spain, the city of his birth, accompanied by a letter of remission, in which he ordered that it be entrusted to his parents, Orencio and Paciencia.

One moment of this pious tradition of the translation of the Holy Chalice from Rome to Huesca, came to be corroborated and portrayed by one of the frescos preserved in the Basilica of St. Laurence Outside the Walls, in which the glorious Deacon is pictured handing to a soldier a chalice with handles, who receives it kneeling, accompanied by another armed soldier who appears to be a witness to the act or guardian of the treasure. Tragically, this fresco disappeared in the bombardment of Rome by the Allies in 1943.

The Holy Chalice was received in Huesca, together with the accompanying letter (unfortunately lost over the course of time), which affirmed among the Christians there the veneration due to such an important relic, which was truly profound, in spite of the need for secrecy and concealment demanded in those times of persecution and other dangers—for example, the terrible and constant persecutions decreed by the Roman Emperors, principally those of Diocletian and Maximian; the frightful battles and apostasies caused by the invasion of barbarians from the North, which subjected the dominion of this region to the Visigoths from the beginning of the 5th century until the invasion of the Moors in the 8th century; the great danger caused by the plunder of Childebert, the King of Paris, who carried off some sixty precious gold chalices from the churches of Spain. Fortunately Huesca was spared the notice of this kleptomaniac king.

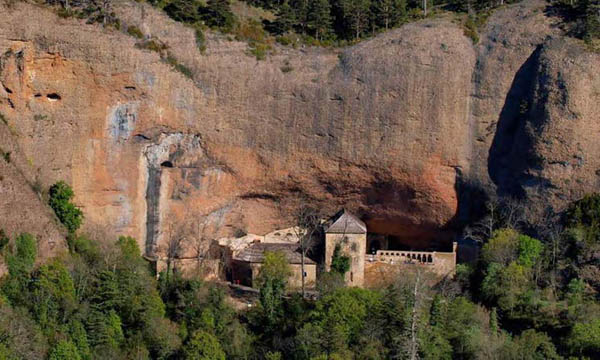

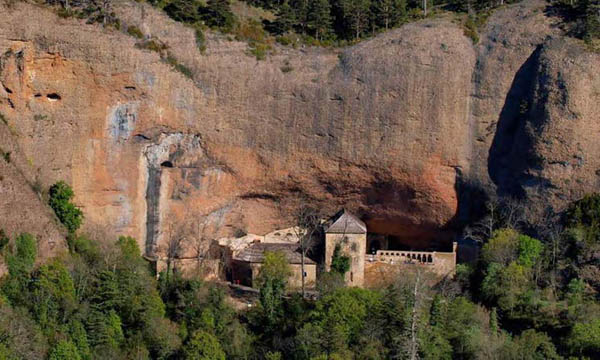

The Holy Chalice remained in Huesca for 450 years until the Moorish invasion of Spain in 711. One year later, the Bishop of Huesca, Acisclo, knowing of the advance of the invaders, decided to abandon the city of Huesca, together with his clergy, soldiers and the people who did not wish to live under the Muslim yoke. They carried with them whatever was most precious from their churches, and above all, the Holy Chalice of the Last Supper. They continued their retreat little by little, in successive steps, through the most hidden trails of the Pyrenees, until they arrived secretly at San Juan de la Peña, a monastery shrouded in mystery and the inspiration of legends, which became the custodian of the precious Relic for 400 years.

History tells us that this Benedictine monastery was founded by King Sancho Garcés on the site of an old hermitage built by a hermit named Juan de Atarés. It is dedicated to St. John the Baptist, and its location, at the foot of a steep cliff some 27 km from Huesca and 16 km from the French border, is nearly hidden from the surrounding highlands. This is the place—hidden, marvelous, secure in spite of its fragility, and remote from those territories still engaged in the struggle with the Moors—where the Sacred Relic was kept for more than 250 years, now under the custody of the cloistered monks, and with the singular affection and protection of the Kings of Aragon, all the more royal for their saintly virtues and their heroic valor, and whose venerable remains still repose in the mausoleum of the monastery.

History tells us that this Benedictine monastery was founded by King Sancho Garcés on the site of an old hermitage built by a hermit named Juan de Atarés. It is dedicated to St. John the Baptist, and its location, at the foot of a steep cliff some 27 km from Huesca and 16 km from the French border, is nearly hidden from the surrounding highlands. This is the place—hidden, marvelous, secure in spite of its fragility, and remote from those territories still engaged in the struggle with the Moors—where the Sacred Relic was kept for more than 250 years, now under the custody of the cloistered monks, and with the singular affection and protection of the Kings of Aragon, all the more royal for their saintly virtues and their heroic valor, and whose venerable remains still repose in the mausoleum of the monastery.

And it will be during this time—a time of epos and grandeur, of faith and heroism—when pilgrimages and crusades are in full vigor, that they will carry with them the notion, laced with fantasy and romance, of the presence of the Holy Chalice amongst jagged peaks; narrations that would give rise to the beautiful and numerous legends of the Holy Grail and its heroes, which jugglers and troubadors would repeat and embellish.

What Legends Tell Us

The fact affirmed by tradition, which establishes the presence of the Holy Chalice, hidden and venerated at San Juan de la Peña during the Reconquista, in conjunction with material from the apocryphal "Gospel of Nicodemas" and the "History of Joseph of Arimathea," probably constitute the basis of a series of legends that spread throughout Europe during the Middle Ages. Such legends, very widespread and of great interest as proof that reinforces the voice of tradition, inasmuch as they are inspired by it, speak of a wonderful Chalice hidden among steep mountains, which was venerated and defended by the Knights of the Holy Grail. The word Grail (Grial in Spanish; Graal in French), used in these legends, has a generic meaning of vessel or cup and is derived from the romance languages of the Hispanic peninsula, as we read in Cervantes, for example. But when the term Holy is added (in Spanish—Santo Grial), it can only refer to the Holy Chalice of the Last Supper.

There are several versions of the legend, principally French and German. The most ancient date back to the 12th century and, in general, tend to be adulterated by extraneous and deformed elements on account of their relationship with various conceptions of King Arthur and the Knights Percival, Lancelot, Galahad, and others. But they always coincide in one common theme: they present to us the deeds of knights and adventurers who begin as fierce warriors and fighters, but transform themselves into virtuous protagonists of valiant acts, motivated by their desire to search for the Sacred Vessel. The various legends had their culmination in the 19th century opera Parsifal (Percival) by Richard Wagner. Perhaps Wagner had better information, for his Percival seeks the Holy Grail in the Pyrenees.

On the other hand, the Bolandists, a group of ecclesiastical writers based in Belgium, who in the 17th century undertook the gigantic task, still unfinished, to pass through the most rigorous sieve of scientific investigation all the sources of history, tradition, and legend referring to the Saints and to Christianity in general, and who left no stone unturned in their formidable and meticulous investigatory labor, when studying everything relative to St. Laurence and confronting the subject of the Holy Chalice, issued this judicious and prudent opinion: "Notwithstanding certain difficulties, it may very well be that the Holy Deacon actually sent the Chalice to Spain, of which he appears to have been a native, and on the other hand, there are no certain documents to be found which convince us of the falsity of this claim; we therefore leave the tradition in the state in which it is."

Percival's exceptional purity obtained for him the grace to see the treasure he longed for, which other virtues could not (lilies elevated above other flowers).

What History Tells Us

There exists a reference from the Canon of Zaragoza, Don Juan Augustín Carreras Ramírez, who in his "Life of St. Laurence", t. I, p. 101, affirms the existence of a church document dated December 14, 1134, according to which it was said in Latin that, "In an ivory case is the Chalice in which Christ Our Lord consecrated His Precious Blood, which was sent by St. Laurence to his fatherland, Huesca." This document would certainly be the first with historical value; but the original has not been found.

Hence it is on September 26, 1399, that there begins the undisputed documentary history of the Holy Chalice, when King Martin "the Humane" learned, shortly after his coronation, that the Holy Chalice of the Lord was preserved in the monastery of San Juan de la Peña. His great piety and devotion to holy relics gave rise to a great desire to possess such a precious jewel. He made a petition to the monks of the monastery, who unanimously decided to satisfy the pious desire of the King. This they did, with the granting of the corresponding public deed that carries the date indicated above, accepting on their part, from the grateful monarch, a splendid gift of a valuable golden chalice—which was melted in the fire suffered by the monastery on November 17, 1494.

The Holy Chalice then went on to be venerated in the Chapel of the Royal Palace of Aljafería, in Zaragoza, together with the other treasures and relics of the Chapel—property of the monarchs of the Crown of Aragon—until King Martin translated his residence to Barcelona, where he died in 1412. He took with him the relics which he possessed, including the Holy Chalice, as is noted in an Inventory of goods made just before the death of the King, in September of 1410.

As a result of the "Compromise of Caspe," headed by St. Vincent Ferrer, his successor in the Kingdom was his nephew, Don Fernando de Antequera, who was followed by his son, Alfonso V, "the Magnanimous." This King was very fond of Valencia and accomplished numerous works of reconstruction therein—such as the exquisite Chapel of the Kings in the convent of St. Dominic. He also had translated to Valencia some magnificent works of art—trophies obtained in his victorious campaigns, as well as a large number of relics, among which the Holy Chalice of the Last Supper figured prominently.

Eventually many of these were situated for greater security in the Cathedral of Valencia. And so we arrive at March 18, 1437, when an inventory was made of the treasury of the Cathedral. In a document notarized by Don Jaime de Monfort, we read of: "the Chalice of our Lord Jesus Christ, consecrated on the day of the Last Supper, with two handles of gold... and adorned with two rubies and two emeralds... and twenty-eight pearls..."

The Holy Chalice remained in the Cathedral of Valencia without interruption until March 18, 1809, when in view of the impending invasion of Napoleon and ensuing military struggles, it was translated to Alicante. From there, after a brief return to Valencia, it was taken to Ibiza and then to Palma de Mallorca. In September of 1813 it was returned again to Valencia—an inventory of that event reads: "#29—The silver box containing the Holy Chalice of the Last Supper."

For more than a hundred years, it was venerated in the Chapel of the Relics within the Cathedral. In 1916 it was moved to its own Chapel (Capilla del Santo Cáliz).

On July 21, 1936, at the beginning of the Spanish Civil War, the Holy Chalice was providentially saved from the burning and sacking of the Cathedral, and thus from imminent profanation and irreparable loss, by the Canons Olmos and Senchermés and Rev. Colomina. They proceeded to hide it, first in various private homes in the city and later amongst the people of Carlet. It remained hidden until March 30, 1939, when peace was restored and it could be returned to Valencia. It could not be returned to the Cathedral until restorations were completed on July 9, 1939.

In 1959, the Holy Chalice made a triumphal return to San Juan de la Peña, in commemoration of the 17th Centenary of the arrival of the Sacred Relic in Aragon. It was carried in procession along many of the same routes it had traversed during those 1700 years. Celebrations were held at every stop, culminating at San Juan de la Peña—the “Covadonga of the Pyrenees”—on June 29. The ceremonies and celebrations continued until July 5, when the Holy Chalice was returned again to the Cathedral of Valencia.

Back to Top

Back to Saints

Contact us: smr@salvemariaregina.info

Visit also: www.marienfried.com

The Evangelists St. Matthew (26: 26-28), St. Mark (14: 22-24) and St. Luke (22: 19-20), as well as St. Paul in his First Epistle to the Corinthians (11: 23-25), relate in a similar manner, and with almost the same words, that the Lord Jesus, being united with His disciples to the celebrate the Pasch, in the night in which He was betrayed, "...took bread, and blessed, and broke, and gave to His disciples, and said: Take ye and eat: This is My Body." And a little later, "And taking the chalice He gave thanks: and gave to them, saying: Drink ye all of this. For this is My Blood of the New Testament, which shall be shed for many, for the remission of sins." (Mt. 26: 26-28)

The Evangelists St. Matthew (26: 26-28), St. Mark (14: 22-24) and St. Luke (22: 19-20), as well as St. Paul in his First Epistle to the Corinthians (11: 23-25), relate in a similar manner, and with almost the same words, that the Lord Jesus, being united with His disciples to the celebrate the Pasch, in the night in which He was betrayed, "...took bread, and blessed, and broke, and gave to His disciples, and said: Take ye and eat: This is My Body." And a little later, "And taking the chalice He gave thanks: and gave to them, saying: Drink ye all of this. For this is My Blood of the New Testament, which shall be shed for many, for the remission of sins." (Mt. 26: 26-28)

—The cup can be dated to between the 4th century B.C. to the 1st century A.D. It is the product of an Egyptian, Syrian, or perhaps a Palestinian workshop, and therefore may very well "have been present on the table of the Last Supper" and "could be that which Jesus Christ made use of to drink, to consecrate, or both."

—The cup can be dated to between the 4th century B.C. to the 1st century A.D. It is the product of an Egyptian, Syrian, or perhaps a Palestinian workshop, and therefore may very well "have been present on the table of the Last Supper" and "could be that which Jesus Christ made use of to drink, to consecrate, or both." The Holy Chalice had remained in Rome for two centuries when there came a period of great violence—beginning with the persecution of Valerian and Gallieno, which surpassed all previous persecutions. The Roman Empire was in a state of economic impotence, and the riches of the Christians, which the persecutors imagined to be fabulous, were considered to be a good remedy. The edict appeared in the year 257 and was repeated in 258. The henchmen of Valerian devoted themselves to the plunder of Christian alms, even to the point of raiding the Catacombs, which were protected by Roman law. Pope St. Sixtus II was incarcerated and condemned to death for refusing to turn over to the Emperor the objects of value owned by the Church. But he still had the means to order his faithful Deacon and Treasurer, St. Laurence, to distribute those goods immediately amongst the poor. The faithful Deacon did so, with the exception of the Holy Chalice (see image right, depicting St. Laurence receiving the Holy Chalice in a locked case and distributing alms), which, moved by a fervent and undoubtedly inspired desire to save it at all costs from the danger facing it in Rome, he sent, two days before his own martyrdom, to Huesca in Spain, the city of his birth, accompanied by a letter of remission, in which he ordered that it be entrusted to his parents, Orencio and Paciencia.

The Holy Chalice had remained in Rome for two centuries when there came a period of great violence—beginning with the persecution of Valerian and Gallieno, which surpassed all previous persecutions. The Roman Empire was in a state of economic impotence, and the riches of the Christians, which the persecutors imagined to be fabulous, were considered to be a good remedy. The edict appeared in the year 257 and was repeated in 258. The henchmen of Valerian devoted themselves to the plunder of Christian alms, even to the point of raiding the Catacombs, which were protected by Roman law. Pope St. Sixtus II was incarcerated and condemned to death for refusing to turn over to the Emperor the objects of value owned by the Church. But he still had the means to order his faithful Deacon and Treasurer, St. Laurence, to distribute those goods immediately amongst the poor. The faithful Deacon did so, with the exception of the Holy Chalice (see image right, depicting St. Laurence receiving the Holy Chalice in a locked case and distributing alms), which, moved by a fervent and undoubtedly inspired desire to save it at all costs from the danger facing it in Rome, he sent, two days before his own martyrdom, to Huesca in Spain, the city of his birth, accompanied by a letter of remission, in which he ordered that it be entrusted to his parents, Orencio and Paciencia. History tells us that this Benedictine monastery was founded by King Sancho Garcés on the site of an old hermitage built by a hermit named Juan de Atarés. It is dedicated to St. John the Baptist, and its location, at the foot of a steep cliff some 27 km from Huesca and 16 km from the French border, is nearly hidden from the surrounding highlands. This is the place—hidden, marvelous, secure in spite of its fragility, and remote from those territories still engaged in the struggle with the Moors—where the Sacred Relic was kept for more than 250 years, now under the custody of the cloistered monks, and with the singular affection and protection of the Kings of Aragon, all the more royal for their saintly virtues and their heroic valor, and whose venerable remains still repose in the mausoleum of the monastery.

History tells us that this Benedictine monastery was founded by King Sancho Garcés on the site of an old hermitage built by a hermit named Juan de Atarés. It is dedicated to St. John the Baptist, and its location, at the foot of a steep cliff some 27 km from Huesca and 16 km from the French border, is nearly hidden from the surrounding highlands. This is the place—hidden, marvelous, secure in spite of its fragility, and remote from those territories still engaged in the struggle with the Moors—where the Sacred Relic was kept for more than 250 years, now under the custody of the cloistered monks, and with the singular affection and protection of the Kings of Aragon, all the more royal for their saintly virtues and their heroic valor, and whose venerable remains still repose in the mausoleum of the monastery.