St. Peter's first sermon.

St. Peter's first sermon.

A. The evidence of Christianity is documentary as well as historic.

I. As in the case of the Mosaic, so also in the case of the Christian revelation, the question arises, on what evidence those facts and circumstances rest by which its divinity is proved. As in the former, so also in the latter case, we must refer to the documents in which those facts are recorded. The arguments thus far advanced, therefore, depend upon the authenticity of the writings of the Apostles and their disciples.

II. The revelation of Christ has this advantage, that it is not only testified by His Apostles and disciples, but has brought about momentous historical facts, which of themselves, independently of the Sacred Writings, would suffice to prove the divinity of its origin. For, the rapid spread of the Christian religion, the direct and indirect testimony of the Martyrs, no less that the writings of the Apostles, give evidence that the Christian religion bears an unmistakably divine character. We are, therefore, justified in adding these proofs to the documentary evidence for the divinity of our religion.

B. The truth of those supernatural facts on which rests the divinity of the Christian religion is proved from the books of the New Testament.

B. The truth of those supernatural facts on which rests the divinity of the Christian religion is proved from the books of the New Testament.

It suffices for our purpose to prove the authenticity of those parts of the New Testament in which the facts establishing the divinity of our religion are related – the Gospels and the Acts of the Apostles. If at times we have appealed to the Epistles of the Apostles, it was only in those cases in which there was sufficient evidence from the Gospels; and our citations have been only from those Epistles against the authenticity of which no serious objections have ever been raised. For the rest, the authenticity of the latter, in general, is based on the same evidence as that of the Gospels and of the Acts.

Taking here for granted what we have shown concerning the twofold authenticity of the Sacred Writings, it is our task to prove the genuineness and integrity of the Gospels and the Acts, and to show the truthfulness of their respective authors.

I. That the said writings are genuine, i.e., composed by the Apostles and their disciples, is testified (a) by Christian antiquity, which either expressly attributes them to the Apostles, or, at least, venerates them as apostolic writings. (b) An imposture would have been impossible during the lifetime of the Apostles, as the latter would manifestly protest; nor could spurious books be subsequently introduced, as the Christians would evidently oppose the introduction of any new and unheard-of writings as coming from the Apostles. The strictness with which the Sacred Writings were tested by the early Church may be inferred from the fact that even some authentic books were in the beginning called into question. (c) Also intrinsic marks go to prove that the books of the New Testament were written in the apostolic times, and either by eye-witnesses or by those who learned the facts immediately from eye-witnesses. So accurate a knowledge of persons, places, and things as is manifested in the Gospels and in the Acts could not well be supposed in others than eye-witnesses. The language used is the so-called Hellenic idiom, abounding in Hebraisms, then common among the Greek-speaking Jews, as may be found in contemporary writers, like Josephus Flavius.

II. A falsification of the books in essential parts would be impracticable. (a) Such a falsification is the less feasible the more numerous the copies of a book are, the more widely it is read, and the more carefully it is guarded against corruption. Now, the books of the New Testament were soon to be found in many hands, and were translated into various languages. They were read in public and in private. Not only the priests, but also the people watched jealously over each word and expression with which they were familiar from childhood; and as soon as heresies sprang up neither the heretics nor the faithful could make any change without being detected. (b) We possess manuscripts, of which some date back to the seventh, some to the sixth and fifth, and some even to the fourth century, which amply testify to the substantial identity of the present with the then existing text. Also the works of the holy fathers, in which the Scriptures are expounded and in great part preserved, bear testimony to the same fact.

III. The truthfulness of the authors is warranted (a) by the testimony of all the converts to Christianity, whether Jews or gentiles, who in accepting the Christian religion professed their belief in the Sacred Books, on whose testimony it mainly rested. (b) As we conclude from the trustworthiness of a book to the truthfulness of its author, so we may, on the other hand, from the truthfulness of the author infer the reliability of the work. Now, the sacred writers could have had sufficient knowledge of the facts they narrate, since they were either eye-witnesses or, at least, learned the facts immediately from eye-witnesses. That they had no intention of deceiving is manifest from a mere glance at the Gospels, for with the greatest uniformity there is sufficient diversity to show that here could have been no conspiracy among them. Everywhere we have the evident marks of sincerity; they reveal the perfidy of Judas, the denial of Peter, and other short-comings of the disciples. And what could induce them to invent facts from which they had nothing to gain but poverty, contempt, persecution, and death?

Even had they wished to do so, they could not have deceived; for the facts in question had taken place before the eyes of many who were still living; and the enemies of the Christianity would certainly have frustrated all attempts at deceit, and corrected exaggerated statements. However, the bitterest enemies of the Christian religion, like Celsus, admitted the truth of the Gospel narratives, while they tried to explain the miracles of Christ as the effects of magic art.

C. The rapid spread of the Christian religion, as testified in history, is an incontrovertible evidence of its divinity.

C. The rapid spread of the Christian religion, as testified in history, is an incontrovertible evidence of its divinity.

The rapid spread of Christianity is testified by St. Paul when he says (Col. 1, 6) that the Gospel is in the whole world, and bringeth fruit and growth.

Tertullian (Apol. c. 37), addressing the pagans, says: We are only of yesterday, and fill all your cities, islands, and fortified places… leaving you only the temples.

And Pliny, Governor of Bithynia (about A.D. 107), writes to the Emperor Trajan that what he calls the Christian superstition had already infected cities, villages,

and country districts (Ep. x 97).

I. Let us first consider the mere natural force of this fact as evidence. When a religion which grounds its truth upon supernatural facts, that is, on signs and miracles, makes such rapid progress, even among cultured nations, in so short a time, we are justified in concluding that those facts were sufficiently established to those who were led by them to embrace that religion. This applies particularly to the Resurrection of Christ, the fundamental proof of His Divinity, to which St. Paul in his preaching chiefly appeals (1 Cor. 1: 23), and which was inserted among the articles of the Apostles' Creed. The conversion of the world is, therefore, a proof that the facts adduced by the Apostles in support of the divine origin of Christianity were acknowledged to be fully established truths.

II. But still greater is the force of this argument if considered from a supernatural standpoint.

A religion which, while professing to be revealed, is propagated in a supernatural manner receives in this divine aid the same sanction as the one professing to be a divine messenger receives by the gift of miracles. Christianity is, therefore, a divine religion if it can be shown that its rapid spread was the work of God. But the miraculous works of Christ and the Apostles as related in Scripture form part of the Christian religion; consequently their truth is also established by all the arguments that go to prove the divine origin of Christianity.

The rapid spread of Christianity will be shown to be a miracle of the moral order if we consider, on the one hand, the inadequacy of the means of overcoming them.

1. These obstacles were partly internal and partly external.

(a) Among the internal obstacles was the Jewish origin of Christianity, which naturally rendered it contemptible to Greeks and Romans. Besides, its dogmas, though in some points perhaps attractive, were, owing to their incomprehensible mysteries, to the necessity of submitting the understanding, and of adoring a crucified God, repulsive to many; while the severity of its morals rendered it distasteful to a sensual generation.

(b) External obstacles originated first from the Jews, who shrank from communion with other nations, clung to their ancient customs, and expected a Messias of earthly splendor. Second, still greater were the obstacles arising from the pagans: from statesmen, who looked on the pagan religion as the bulwark of Roman power; from the priests, who derived emolument and influence from the pagan religion; from the philosophers, who, depraved with sensuality or puffed up with self-conceit, were unwilling to submit to the folly of the cross; from the artists who were employed in the service of idolatry; from the people, in fine, who, though estranged from the pagan religion, yet delighted in the revelry of pagan feasts.

2. The rapid diffusion of Christianity in spite of these difficulties cannot be ascribed to natural causes. The unity of the empire, which afforded a certain facility of intercourse, favored, but could not effect this extension, and was, on the other hand, a hindrance, since it afforded equal opportunity of persecuting Christianity. The general disposition might be said to be favorable, inasmuch as a conviction of the futility of paganism prevailed; but irreligion and indifference were, again, a serious obstacle. Commercial enterprise and military expeditions may have diffused some knowledge of Christianity; but with this knowledge were disseminated also the strongest prejudices against it. The charity of the Christians might attract some; but not all converts needed assistance; the means of the early Christians were limited, and conversions from motives of self-interest would not have been lasting in times of persecution. If, finally, we attribute the rapid spread of Christianity to the gift of miracles, possessed by the Apostles and their disciples, we thereby acknowledge its divinity, as well as the truth of those facts upon which it rests. We may apply to the spread of Christianity St. Augustine's argument for the truth of the Resurrection of Christ: Either Christianity was miraculously propagated, and is, therefore, of divine origin; or it was not miraculously propagated, and in this case its extension is for that very reason much the more a miracle (de Civ. Dei xxii, c. 5).

If other religions, e.g. Islam, have had a speedy extension, the causes, on reflection, will be found to be natural. Such religions had few dogmatic truths, flattered the sensual cravings of man, were favored by those in power, were imposed by force, or offered temporal advantages.

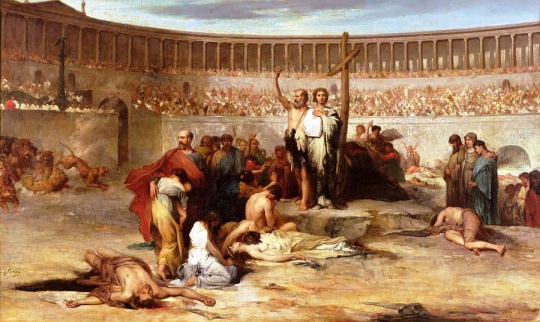

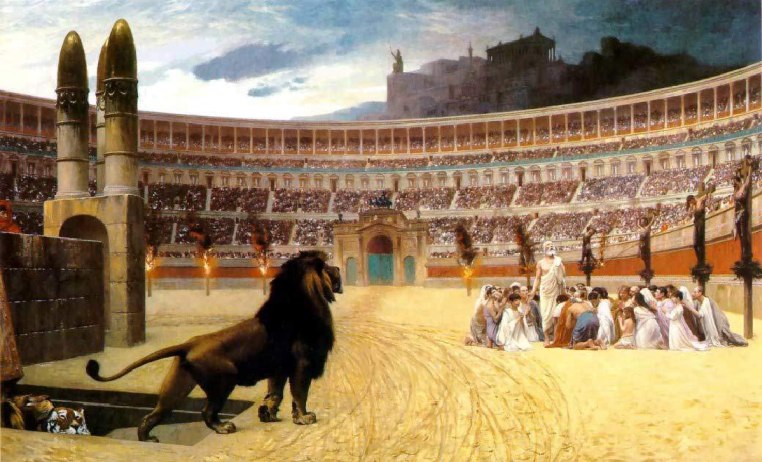

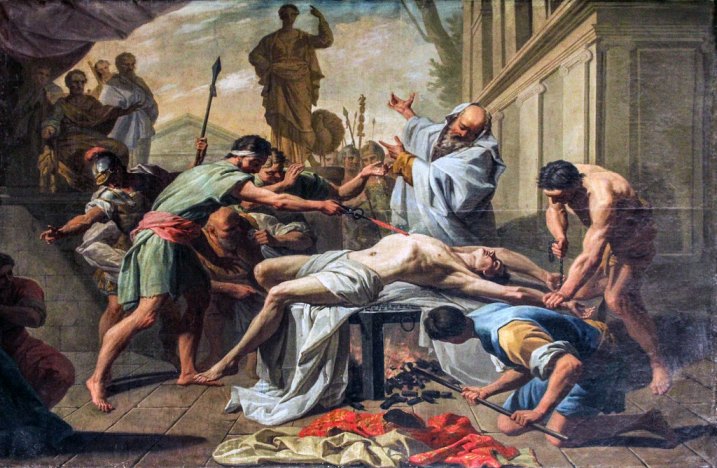

D. The divinity of the Christian religion is proved by the testimony of the Martyrs.

The Martyrs of early Christian times may be regarded from a natural and from a supernatural standpoint. Regarded from a natural point of view, in spite of tortures and even death, they professed their conviction of the truth of those facts upon which the Christian religion is founded. As such they are, in the ordinary sense of the word, witnesses to those facts. Regarded from a supernatural point of view, they displayed a fortitude resulting, not from human, but from divine power. In this respect their fortitude is a miracle of the moral order, wrought by God in testimony of the truth of that religion for which they suffered and died, and, at the same time, in testimony of those facts upon which this religion is based.

I. A testimony which would be sufficient to substantiate any other fact of moment must also suffice as proof of those facts to which Christianity appeals as evidence of its divinity. Now, the testimony of the Martyrs is doubtless such as would suffice to establish any other fact as certain; consequently, it is sufficient as evidence of those facts which form the groundwork of the Christian religion.

The testimony of the Martyrs possessed all those qualities which we can require in evidence:

1. First, as regards the number of the witnesses; it was, according to the records of Christian and pagan writers, extraordinary. Many of them were eye-witnesses of the works of Christ; as, for instance, the Apostles, and the other disciples who, like them, gave their lives for their Faith. Others, again, were eye-witnesses of the miracles wrought by the Apostles and by their disciples. Still greater was the number of indirect witnesses, i.e., of such as, convinced by the testimony of others who had seen the miracles of the Apostles and disciples, embraced Christianity in later times. Many of these were also eye-witnesses of miracles wrought by the preachers of the Faith; for the gift of miracles was not infrequent in the early ages of Christianity.

2. If we next consider the personal qualities of the witnesses, they certainly possessed both a sufficient knowledge of what they testified and sufficient probity to testify to the truth. There was question of conspicuous patent facts, a knowledge of which was not only easy to obtain, but even forced itself on the observer, and challenged investigation. Besides, there is no doubt that a witness means to tell the truth as often as his testimony, far from bringing him any advantage, entails the loss of property, and of life itself. This was the case with the Martyrs.

The difference between the testimony of the Martyrs and that of fanatics who have given their lives for false opinions is this: the Martyrs bore testimony of facts; fanatics, at most, to their own convictions. Death for one's opinion is no proof of its truth; but the testimony to a fact connected with heroic sacrifice of property or life is acknowledged by all to have the greatest weight.

II. The fortitude displayed by the Martyrs is a miracle of the moral order wrought by God, and as such evidence of the divine origin of Christianity, and, consequently, also of the truth of those supernatural facts on which it rests, and which form part of its teaching.

It matters not whether the Martyrs died for the truth of the Christian religion itself, or for some particular dogma, or some Christian virtue. They died, in any case, for Christianity. Nor does it matter whether they belonged to early or later times; for, since the evidence is taken from the fortitude of the Martyrs, not from their formal testimony to particular facts, its force is the same. We emphasize, however, the extraordinary number of the Martyrs, because, there being question of the supernatural, the inefficiency of natural causes is more evident in the case of many than in the case of a few, which might be accounted exceptional.

Men do not patiently submit to suffering, torture, and ignominious death without some powerful motive. This powerful motive must be either a natural or a supernatural one. In the case of the Christian Martyrs it was not a natural motive, i.e., founded upon natural causes, but a supernatural, extraordinary, marvelous effect of grace.

1. This follows from the declaration of the Martyrs themselves, who frequently assured that it was only by strength from on high that they endured their torments. Besides, it happened not unfrequently that those who trusted too much to their own strength fell off under tortures. Even the pagans themselves frankly acknowledged that the Martyrs were incapable of enduring such torments without the special help of God. Much more forcibly do the pagans confess this conviction by the fact that, influenced by the marvelous constancy of the Martyrs, they themselves embraced Christianity.

2. That the constancy of the Martyrs was not inspired by natural motives is evident from the very nature of the case. For what natural motives would have been sufficient to influence them?

(a) Not vainglory; for among them were many who were insensible to this motive; for instance, children, slaves, and men of the lowest rank, many of whom died so utterly unknown that not even their names are recorded. From martyrdom many, instead of honor, reaped only shame. Therefore, though the founders of certain sects, though individuals may have given their lives for their religious opinions from motives of ambition, yet in the case of the Christian Martyrs such a supposition is, for the reasons alleged, inconceivable.

(b) Not the prospect of religious veneration; for many of them knew that this veneration could never be paid to them, since their name and their resting-place were quite unknown. Indeed, owing to the great number of the Martyrs, it often happened that death for the Faith received little notice.

(c) Not the hope of a happy eternity, as a natural motive, influenced the Christian Martyrs, as the prospect of a sensual paradise fired the followers of Mahomet (e.g., suicide bombers. True, the Martyrs had the prospect of an eternal reward, which as a supernatural motive, in union with the grace of God, sustained them; but this hope alone, as a mere natural motive, could not produce in them such extraordinary fortitude, because the goods which were promised them were of a spiritual order, and, therefore, less apt to move the sensual man than those pleasures which Mahomet pretended to secure to his followers. Nay, the very understanding of those spiritual and supernatural goods is the work of God, Who, besides, must aid the weak will of man that he may not, in spite of the hope of heavenly joys, be overcome by present sufferings.

(d) Not fanaticism; for fanaticism urges to action and combat, as it did the followers of Mahomet and of Huss; or, if at times it enables some, like the Brahmins, to bear extraordinary torture, it always betrays a tendency to seek admiration. Fanaticism is always attended with other passions; it deprives man of self-possession, produces morbid excitement, and is of short duration. But the calm self-possession which the Martyrs always maintained shows how far removed they were from any kind of fanaticism.

3. God showed by evident signs that it was He Who strengthened the Martyrs in their conflicts. Now He revealed to them the day of their death; now He comforted them by a voice from Heaven; now He freed them from all sense of pain; now He took from their torturers the power to hurt them; now He visited apostates with supernatural punishments before the eyes of all.

It is evident that this miracle which we behold in the fortitude of the Martyrs is incontrovertible evidence of the truth of the Christian religion and of the divinity of its origin. For God could not by miracle encourage the faithful to persevere in a false religion. But by the supernatural fortitude of the Martyrs, consequently by God's doing, the Christian religion was strengthened and augmented by the accession of countless thousands, who, invincibly drawn by the example of the Martyrs, beheld in Christianity a divine institution. This effect, the natural outcome of such a miracle, must have been intended by God; whence we must conclude that God, by working this miracle through His servants, bore testimony to the truth of Christianity, and thus confirmed those supernatural facts on which rests the evidence of the Christian Religion.

Alphabetical Index; Calendar List of Saints

Contact us: smr@salvemariaregina.info

Visit also: www.marienfried.com