Great and St. Pius V; it bids us today to pay honor to the glorious memory of St. Gregory VII. These three names represent the action of the papacy, dating from the period of the persecutions. The mission divinely put upon the successors of St. Peter, simply put, is this: to maintain intact the truths of the Faith, and to defend the liberty of the Church. St. Leo courageously and eloquently asserted the ancient Faith, which was called into question by the heretics of those days; St. Pius V stemmed the torrent of the Protestant revolution, and delivered Christendom from the yoke of Islam; St. Gregory VII came between these two, and saved society from the greatest danger it had so far incurred, and restored the purity of Christian morals by restoring the liberty of the Church.

The end of the 10th and the commencement of the 11th century was a period that brought upon the Church of Christ one of the severest trials She has ever endured. The two great scourges of persecution and heresy had subsided; they were followed by that of barbarism. The impulse given to civilization by St. Karl the Great (Charlemagne) was halted later in the 9th century—the barbarian element had just been suppressed, when it broke out again with renewed violence. Faith was still vigorous among the people, but of itself it could not triumph over the depravity of morals. The feudal system of that time tended to produce anarchy throughout the whole of Europe; anarchy created social disorder, and this, in its turn, occasioned the triumph of might and licentiousness over right. Kings and princes were no longer kept in check by the power of the Church; for Rome herself being a prey to factions, unworthy or unfit men were too frequently raised to the Papal Throne.

The 11th century came; its years were rapidly advancing; and there seemed no remedy for the disorders it had inherited. Bishoprics had fallen a prey to the secular power (who had, as a ready excuse, a need to suppress anarchy), which set them up for sale, and the first requisite for a candidate to a prelacy was that he should be a vassal subservient to the ruler of the nation, ready to supply him with means for prosecuting war. The bishops being thus, to a great extent, simoniacal, as St. Peter Damian tells us they were, what could be expected from the inferior clergy but scandals? The climax of these miseries was that ignorance increased with each generation, and threatened to obliterate the very notion of duty. Had it not been for the promise of Christ that He would never abandon His own work, it would have seemed the end to both Church and Christian society.

In order to remedy these evils, in order to dispel all this mist of ignorance, Rome had to be raised from her state of degradation. She needed a holy and energetic Pontiff, whose reign should be long enough to make his influence felt, and encourage his successors to continue the work of reform. This was the mission of St. Gregory VII.

This mission was prepared for by holiness of life; it is always so with those whom God destines to be the instruments of His greatest works. Gregory, or as he was then called, Hildebrand, left the world, and became a monk of the celebrated monastery of Cluny in France. It was there, and in the two thousand abbeys which were affiliated with it, that were alone to be found in those days zeal for the liberty of the Church, and the genuine traditions of the monastic life. It was there that for upwards of a hundred years, and under the four great Abbots, St. Odo, Maiolus, St. Odilo and St. Hugh, God had been secretly providing for the regeneration of Christian morals. Yes, we may well say secretly, for no one would have thought that the instruments of the holiest of reforms were to be found in those monasteries, which existed in almost every part of Europe, and had affiliated with Cluny for no other motive than because Cluny was the sanctuary of every monastic virtue. It was to Cluny itself that Hildebrand fled, when he left the world; he felt sure that he would find there a shelter from the scandals that then prevailed.

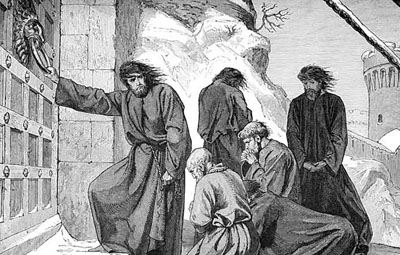

The illustrious Abbot Hugh was not long in discovering the merits of his new disciple, and the young Italian was made Prior of the great French abbey. A stranger came one day to the gate of the monastery, and sought hospitality. It was Bruno, Bishop of Toul, who had been nominated Pope by the Emperor Henry III. Hildebrand could not restrain himself on seeing this new candidate for the Apostolic See—whom Rome, which alone has the right to choose its own Bishop, had neither chosen nor heard of. He plainly told Bruno that he must not accept the Keys of Heaven from the hand of an Emperor who was bound in conscience to submit to the canonical election of the holy City. Bruno, who was afterwards St. Leo IX, humbly acquiesced in the advice given him by the Prior of Cluny, and both set out for Rome. The elect of the Emperor became the elect of the Roman Church, and Hildebrand prepared to return to Cluny; but the new Pontiff would not hear of his departure, and obliged him to accept the title and duties of Archdeacon of the Roman Church.

This high post would soon have raised him to the Papal Throne, had he wished it; but Hildebrand's only ambition was to break the fetters that kept the Church from being free, and prepare the reform of Christendom. He used his influence in procuring the election, canonical and independent of imperial favor, of Pontiffs who were willing and determined to exercise their authority for the extirpation of scandals. After St. Leo IX came Victor II, Stephen IX, Nicholas II and Alexander II—all of whom were worthy of their exalted position. But he who had thus been the very soul of the Pontificate under five Popes was at length obliged to accept the Tiara himself. His noble heart was afflicted at the presentiment of the terrible contests that awaited him; but his refusals, his endeavors to evade the heavy burden of solicitude for all the Churches, were unavailing; and the new Vicar of Christ was made known to the world under the name of Gregory VII. "Gregory" means vigilance; and never did man better realize the name.

He had to contend with brute force personified in a daring and crafty Emperor, whose life was stained with every sort of crime, and who held the Church in his grasp, as a vulture does its prey. In no part of the Empire would a bishop be allowed to hold his see, unless he had received investiture from the Emperor, by the ring and crosier. Such was Henry IV of Germany; and his example encouraged the other princes of the Empire to infringe on the liberty of canonical elections by the same iniquitous measures. The twofold scandal of simony and incontinence was still frequent among the clergy. St. Gregory's immediate predecessors had, by courageous zeal, checked the evil; but not one of them had ventured to confront the fomenter of all these abuses, the Emperor himself. The great contest, with its perils and anxieties, was left to St. Gregory; and history tells us how fearlessly he accepted it.

The first three years of his pontificate were, however, comparatively tranquil. St. Gregory treated the youthful Emperor with great kindness, out of regard for his father Henry III, who was surnamed the Pious. He wrote him several letters, in which he gave him good advice, or affectionately expressed his confidence in the future. Henry did not allow that confidence to last long. Aware that he had to deal with a Pope whom no intimidation could induce to swerve from duty, he thought it prudent to wait a while and watch the course of events. But the restraint was unbearable; the self-imposed check had but swelled the torrent; the enemy of the spiritual power gave full vent to his passion. Bishoprics and abbeys were again sold for the benefit of the imperial revenue. St. Gregory excommunicated the simoniacal prelates; and Henry, imprudently defying the censures of the Church, persisted in keeping in their posts men who were resolved to follow him in all his crimes. St. Gregory addressed a solemn warning to the Emperor, enjoining him to withdraw his support from the excommunicated prelates, under the penalty of himself incurring the ban of the Church. Henry, who had thrown off the mask, and thought he might afford to despise the Pope, was unexpectedly made to tremble by the revolt of Saxony, in which several of the Electors of the Empire joined. He felt that a rupture with the Church at such a critical time might be fatal. He turned suppliant, besought St. Gregory to absolve him, and made an abjuration of his past conduct in the presence of two Legates, sent by the Pontiff into Germany. But scarcely had the perjured monarch gained a temporary triumph over the Saxons than he recommenced hostilities with the Church. In an assembly of bishops, worthy of their imperial master, he presumed to pronounce sentence of deposition against St. Gregory. Shortly afterwards he entered Italy with his army; and this gave to scores of prelates an opportunity for openly declaring rebellion against the Pope, who would not tolerate their scandalous lives.

Thus did St. Gregory, in whose hands were placed those keys which signify the power of loosing and binding in Heaven and on earth, pronounce against Henry the terrible sentence which declared him to be deprived of his crown and to have forfeited the allegiance of his subjects. To this the Pontiff added the still heavier anathema; he declared him to be cut off from the communion of the Church. By thus setting himself as a rampart of defense to Christendom, which was threatened on all sides with tyranny and persecution, Gregory drew down upon himself the vengeance of every wicked passion; and even Italy was far from being as loyal to him as he had a right to expect her to be. More than one of the princes of the peninsula sided with Henry; and as to the simoniacal prelates, they looked on him as their defender against the sword of St. Peter. It seemed as though St. Gregory would soon not have a spot in Italy whereon he could set his foot in safety; but God, who never abandons His Church, raised up an avenger of His cause. Tuscany, and part of Lombardy, were, at that time, governed by the young and brave Countess Matilda. This noble-hearted woman stood up in defense of the Vicar of Christ. She offered her wealth and her army to the Pope, that he might make use of them as he thought best, for as long as she lived; and as to her possessions, she willed them to St. Peter and his successors.

Matilda, then, became a check to the Emperor's prosperity in crime. Her influence in Italy was still strong enough to procure for the heroic Pontiff a refuge where he could be safe from the Emperor's power. He was enabled by her management to reach Canossa, a strong fortress near Reggio. At the same time, Henry was alarmed by news of a fresh revolt in Saxony, in which more than one feudal lord of the Empire took part, with a view to dethrone the haughty and excommunicated tyrant. Fear again took possession of his mind, and prompted him to recur to perjury. The spiritual power marred his sacrilegious plans; and he flattered himself that by offering a temporary atonement he could soon renew the attack. He went barefoot and unattended to Canossa, garbed as a penitent, shedding hypocritical tears, and suing for pardon. St. Gregory had compassion on his enemy, and readily yielded to the intercession made for him by Hugh of Cluny and Matilda. He removed the excommunication and restored Henry to the pale of Holy Church; but thought it would be premature to revoke the sentence whereby he had deprived him of his rights as Emperor. The Pontiff contented himself with announcing his intention of assisting at the Diet which was to be held in Germany; there he would take cognizance of the grievances brought against Henry by the Princes of the Empire, and then decide what was just.

Matilda, then, became a check to the Emperor's prosperity in crime. Her influence in Italy was still strong enough to procure for the heroic Pontiff a refuge where he could be safe from the Emperor's power. He was enabled by her management to reach Canossa, a strong fortress near Reggio. At the same time, Henry was alarmed by news of a fresh revolt in Saxony, in which more than one feudal lord of the Empire took part, with a view to dethrone the haughty and excommunicated tyrant. Fear again took possession of his mind, and prompted him to recur to perjury. The spiritual power marred his sacrilegious plans; and he flattered himself that by offering a temporary atonement he could soon renew the attack. He went barefoot and unattended to Canossa, garbed as a penitent, shedding hypocritical tears, and suing for pardon. St. Gregory had compassion on his enemy, and readily yielded to the intercession made for him by Hugh of Cluny and Matilda. He removed the excommunication and restored Henry to the pale of Holy Church; but thought it would be premature to revoke the sentence whereby he had deprived him of his rights as Emperor. The Pontiff contented himself with announcing his intention of assisting at the Diet which was to be held in Germany; there he would take cognizance of the grievances brought against Henry by the Princes of the Empire, and then decide what was just.

Henry accepted every condition, took his oath on the Gospel, and returned to his army. He felt his hopes rekindle within him at every step he took from the dreaded fortress, within whose walls he had been compelled to sacrifice his pride to his ambition. He reckoned on finding support from the bad passions of others, and to a certain extent his calculation was verified. Such a man was sure to come to a miserable end; but Satan was too deeply interested in his success to refuse him his support.

Henry accepted every condition, took his oath on the Gospel, and returned to his army. He felt his hopes rekindle within him at every step he took from the dreaded fortress, within whose walls he had been compelled to sacrifice his pride to his ambition. He reckoned on finding support from the bad passions of others, and to a certain extent his calculation was verified. Such a man was sure to come to a miserable end; but Satan was too deeply interested in his success to refuse him his support.

Meanwhile, Henry was challenged by a rival in Germany: it was Rodolph, Duke of Swabia, who, in a Diet of the Electors of the Empire, was proclaimed Henry's successor. Faithful to his principles of justice, St. Gregory refused, at first, to recognize the newly elected, although his devotion to the Church and his personal qualifications were such as to make his most worthy of the throne. The Pope persisted on hearing both sides, that is, the princes and representatives of the Empire, and Henry himself; this done, he would put an end to the dispute by an equitable judgment. Rodolph strongly urged his claims, and importuned the Pontiff to recognize them; but St. Gregory, though he loved the duke, courageously refused his demand, assuring him that his cause should be tried at the Diet by which Henry had bound himself, by his oath at Canossa, to stand, though he had good reasons to fear its results. Three years passed on, during which the Pontiff's patience and forbearance were continually tried by Henry's systematic subterfuges, and refusal to give guarantees against his further molesting the Church. At length, after using every means in his power to put an end to the wars that ravaged Italy and Germany, and after Henry had given unmistakable proofs of impenitence and perjury, the Pontiff renewed the excommunication, and in a Council held at Rome, confirmed the sentence whereby he had declared him deposed of his crown. At the same time, St. Gregory ratified Rodolph's election, and granted the Apostolic benediction to his adherents.

Henry's rage was at its height, and his vengeful temper threw off all restraint. Among the Italian prelates who had sided with the tyrant, the foremost in subservience and ambition was Gilbert, Archbishop of Ravenna, and, of course, there was no more bitter enemy to the Holy See. Henry made an anti-pope of this traitor, under the name of Clement III. He had his partisans; and thus schism was added to the other trials that afflicted the Church. It was one of those terrible periods when, according to the expression of the Apocalypse, it was given unto the Beast to make war with the Saints, and to overcome them (13: 7). The Emperor suddenly became victorious: Rodolph was slain fighting in Germany, and Matilda's army was defeated in Italy. Henry had then one wish, and he determined to realize it: to enter Rome, banish Gregory, and set his anti-pope on the Chair of St. Peter.

St. Gregory preserved the simplicity of a monk amidst all his occupations as Pope; and what engrossing occupations were these, even apart from that fearful contest with tyranny and crime which cost him his life! He it was who first began to plan the project of the Crusade, which, at a later period, was enough to immortalize the name of Pope Urban II. As to his other labors for the good of religion in every part of Christendom, we may truly say that at no period of the Church's existence did the papacy exercise a wider, more active, or more telling influence, than during the twelve years of his pontificate. By his immense correspondence, he furthered the interests of the Church in Germany, Italy, France, England and Spain; he aided the rising Churches of Denmark, Sweden and Norway; he testified his vigilant and tender solicitude for the welfare of Hungary, Bohemia, Poland, Serbia, yes, even for Russia. Despite the rupture between Rome and Byzantium, the Pontiff withheld not his paternal intervention with a view to remove the schism which kept the Greek Church out of the center of unity. On the coast of Africa, he, by great vigilance, succeeded in maintaining three bishoprics which had survived the Muslim invasion. In order to knit the Latin Church into closer unity by greater unity in prayer, he abolished the Gothic Liturgy that was used in Spain, and forbade the introduction of the Greek Liturgy into Bohemia. What work was this for one man! And what a martyrdom he had to suffer! But let us resume our history of his trials.

Henry marched on towards Rome, taking with him the anti-pope. He set fire to that part of the City which would expose the Vatican to danger. St. Gregory sent his blessing to his terrified people, and immediately the fire took the contrary direction and died out. Enthusiasm filled, for a while, the hearts of the Romans, who have so often been ungrateful to their Pontiff. Henry was afraid to consummate the sacrilege. He therefore sent word to the Romans that he only asked one condition; it was that they should induce St. Gregory to consecrate him Emperor of Germany, and that he would forever be a devoted son of the Church: as to the ignoble phantom he had set up in opposition to the true Pope, he (Henry) would see that he was soon forgotten. This petition was presented to St. Gregory by the whole City. The Pope made this reply: "Too well do I know the king's treachery. Let him first make atonement to God and to the Church which he tramples beneath his feet. Then will I absolve him, if penitent, and crown the convert with the imperial diadem." The Romans were earnest in their entreaties, but this was the only answer they could elicit from the inflexible guardian of Christian justice. Henry was about to withdraw his troops, when the fickle Romans, bribed by money from Byzantium (for then, as ever, all schisms were in fellowship against the Papacy), abandoned their spiritual King and Father, and delivered up the keys of the City to him who enslaved their souls. St. Gregory was thus obliged to seek refuge in Castle Sant'Angelo, taking with him into that fortress-prison the liberty of Holy Church.

From that fortress, he could hear the impious cheers of his people as they followed Henry to the Vatican Basilica, where, at St. Peter's Confession, the mock pope was awaiting his arrival. It was Palm Sunday of 1085. The sacrilege was committed. On the previous day, Gilbert dared to ascend the Papal Throne in the Basilica of St. John Lateran; on this day, whilst the people held in their hands the palms that should glorify the Christ, whose Vicar was St. Gregory, the anti-pope took the crown of the Christian Empire and put it on the head of the excommunicated Henry. But God was preparing an avenger of His Church. The true Pope was kept a close prisoner in the fort, and it seemed as though his enemy would soon make him a victim of his rage; when the report suddenly spread through Rome that Robert Guiscard, the valiant Norman chieftain, was marching on towards the City. He had come to fight for the captive Pontiff, and deliver Rome from the tyranny of Henry. The false Caesar and his false pope were panic-stricken; they fled, leaving the perjured City to expiate its odious treason in the horrors of a ruthless pillage.

St. Gregory's heart bled at seeing his people thus treated. It was not in his power to prevent the depredations of the barbarian troops; they had done their work of delivering him from his enemies, but they were not satisfied. They had come to Rome to chastise Her, but now they wanted booty, and they were determined to have it. Not only was the Saint powerless to repress these marauders; he was in danger of again falling into Henry's hands, who was meditating a return to Rome, for he made sure that the people's angry humor would secure him a welcome back, and that the Normans would withdraw from the City as soon as it had no more to give them. St. Gregory, therefore, overwhelmed with grief, left the capital; and, shaking off the dust from his feet, he repaired to Monte Cassino, where he sought shelter and a few hours' repose with the sons of the great Patriarch St. Benedict.

St. Gregory's heart bled at seeing his people thus treated. It was not in his power to prevent the depredations of the barbarian troops; they had done their work of delivering him from his enemies, but they were not satisfied. They had come to Rome to chastise Her, but now they wanted booty, and they were determined to have it. Not only was the Saint powerless to repress these marauders; he was in danger of again falling into Henry's hands, who was meditating a return to Rome, for he made sure that the people's angry humor would secure him a welcome back, and that the Normans would withdraw from the City as soon as it had no more to give them. St. Gregory, therefore, overwhelmed with grief, left the capital; and, shaking off the dust from his feet, he repaired to Monte Cassino, where he sought shelter and a few hours' repose with the sons of the great Patriarch St. Benedict.

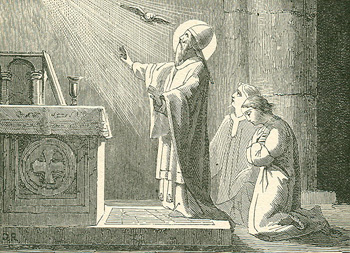

Before descending the holy mount, he was honored with the miraculous manifestations which had been witnessed on several previous occasions. St. Gregory was at the Altar, offering up the Holy Sacrifice, when suddenly a white dove was seen resting on his shoulder, with its beak turned towards his ear, as though it were speaking to him. It was not difficult to recognize, under this expressive symbol, the guidance which the saintly Pontiff received from the Holy Ghost.

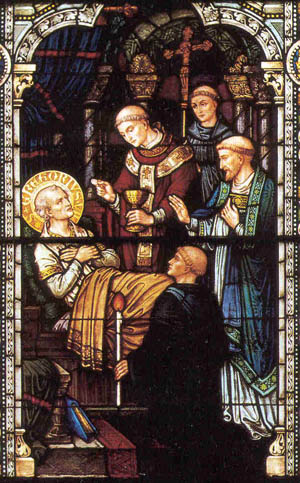

St. Gregory then repaired to Salerno, where his troubles and life were to be brought to a close. His bodily strength was gradually failing. He insisted, however, on going through the ceremony of the dedication of the Church of St. Matthew the Evangelist, whose body was kept at Salerno. He addressed a few words in a feeble voice to the assembled people. He then received the Body and Blood of Christ. Fortified with this life-giving Viaticum, he returned to the house where he was staying, and threw himself upon the couch, whence he was never to rise again. There he lay, like Jesus on His Cross, robbed of everything, and abandoned by almost the whole world. His last thoughts were for Holy Church. He mentioned to the few Cardinals and Bishops who were with him, three from whom he would recommend his successor to be chosen: Desiderius, Abbot of Monte Cassino, who succeeded him under the title of Victor III; Otho of Chatillon, a monk of Cluny, who was afterwards Urban II, Victor's successor; and the faithful legate, Hugh of Die, whom St. Gregory had made Archbishop of Lyons.

St. Gregory then repaired to Salerno, where his troubles and life were to be brought to a close. His bodily strength was gradually failing. He insisted, however, on going through the ceremony of the dedication of the Church of St. Matthew the Evangelist, whose body was kept at Salerno. He addressed a few words in a feeble voice to the assembled people. He then received the Body and Blood of Christ. Fortified with this life-giving Viaticum, he returned to the house where he was staying, and threw himself upon the couch, whence he was never to rise again. There he lay, like Jesus on His Cross, robbed of everything, and abandoned by almost the whole world. His last thoughts were for Holy Church. He mentioned to the few Cardinals and Bishops who were with him, three from whom he would recommend his successor to be chosen: Desiderius, Abbot of Monte Cassino, who succeeded him under the title of Victor III; Otho of Chatillon, a monk of Cluny, who was afterwards Urban II, Victor's successor; and the faithful legate, Hugh of Die, whom St. Gregory had made Archbishop of Lyons.

The bystanders asked the dying Pope what were his wishes regarding those whom he had excommunicated. Here again he imitated our Savior on his Cross—he exercised both justice and mercy. "Excepting," said he, "Henry and Gilbert, the usurper of the Apostolic See, and them that connive at their injustice and impiety, I absolve and bless all those who have faith in my power, as being that of the holy Apostles Peter and Paul." Calling to him, one by one, the faithful few who stood round his couch, he made them promise on oath that they would never acknowledge Henry as Emperor until he had made satisfaction to the Church. Summing up all his energy, he solemnly forbade them to recognize anyone as Pope unless he were elected canonically and in accordance with the rules laid down by the holy Fathers. Then, after a moment of devout recollection, he expressed his conformity with the Divine Will, which had ordained that his pontificate should be one long martyrdom, and said: "I have loved justice and hated iniquity: for this cause, I die in exile!" One of the bishops who were present, respectfully made him this reply: "No, my lord, you cannot die in exile: for holding the place of Christ and the holy Apostles, you have had given to you the nations for your inheritance, and the utmost parts of the earth for your possession." Sublime words! But St. Gregory heard them not: his soul had winged its flight to Heaven, and had received a martyr's immortal crown.

Contact us: smr@salvemariaregina.info

Visit also: www.marienfried.com