In this series, condensed from a book written by Fr. Northcote prior to 1868 on various famous Sanctuaries of Our Lady, the author succeeds in defending the honor of Our Blessed Mother and the truth of the Catholic Faith against the wily criticism of many Protestants.

In the present chapter we propose noticing a few of those passages which occur in early English historians, or in the lives of our English Saints, wherein allusion is made to churches or images of Our Lady the precise locality of which is not always given. Our early biographies and histories are full of such allusions, and much as we should desire to be furnished with more exact information regarding these ancient sanctuaries, the imperfect accounts which are all that are left us, suffice to show how numerous they were, and how deeply rooted was the devotion with which they were regarded by the populace.

And first we may instance some of the legends of the early life of St. Thomas of Canterbury (Becket), who appears to have acquired his very special devotion to the Blessed Virgin from the teaching of his mother. One of the modes by which she displayed her devotion was common enough in Catholic England, and singularly characteristic of old English piety, wherein, mingled with what was tender and poetical, there was generally to be found a certain homely simplicity, which always contrived to keep in mind the alliance between prayer and almsdeeds.

The Saint's mother was used to put her son at certain times into the scales, and to weigh him with clothes, meat, bread, and money,

which were placed in the opposite scale. These things were then distributed to the poor, and her intention was by this act to

commend him to the protection of God, and the prayers of the Blessed Virgin. For, says Roger de Pontigny, among the works of piety

that she exercised, she had a very special devotion to the Blessed Virgin, and carefully taught her son (as he was accustomed ofttimes

to say) to fear God, and to love and venerate the Blessed Virgin Mary with special devotion, and to invoke Her as the Patroness and

Mistress of all his life and acts, and to make Her his hope next to Our Lord Jesus Christ.

We are told that in his youth St. Thomas received some very precious marks of Our Lady's favor: one was,

that being ill of a fever She appeared to him, promised him that he should recover, and placed in his hands two golden keys,

as if to indicate his future greatness. The other occurred when he was at school – we are not told whether at Merton or in London,

but the incident plainly belongs to the period of his boyhood. Playing with some other youths of his own age, his companions began

to praise, some one, and some another fair lady of their acquaintance, and after the fashion of the times to exhibit the gloves

or other favors

which they had received from the object of their admiration, or which they wore in her honor. But St. Thomas,

being required to show the like, answered that he had given his heart to a Lady of far higher degree, and being urged by his comrades

to show some token of Her favor, he retired into a church, and praying before an image of the Blessed Virgin, who was in truth the

Lady to whom he had vowed his love, he returned to his schoolfellows with a glowing countenance as one who had been granted a

heavenly grace, and exhibited to them a little box containing a cope of red color (a token apparently of his future dignity

and martyrdom), which he declared to them was the pledge of affection which he had received from the Lady of his heart.

Another story in his life has the same homely and familiar character before noted. The light-hearted youth of whom his biographer says, that he cared for nothing so much as dogs and birds, was even from his boyhood addicted to secret acts of penance. When Primate of Canterbury, he was accustomed to wear a hair-shirt under his costly garments, and once, it is said, the hair-shirt requiring mending, the Saint was both unable to do this himself and unwilling to call in the aid of others, lest the secret of that austerity, which he so jealously concealed from the world at large, should become blazed abroad. And on this occasion, says his biographer, Our Lady came to his aid, and sewed the hair-shirt with Her own hands.

The favorite devotion with which St. Thomas was accustomed to invoke his great Patroness, was the salutation of

Her Seven Joys, and we read how on one occasion Our Lady appeared to him, and after assuring him that his homage was most pleasing

to Her, inquired of him why he only commemorated Her Joys on earth, and not also those which formed Her crown in Heaven;

and he replying that he knew not which they were, She made known to him Her Seven Celestial Joys, after which time the Saint

constantly honored them, and composed the Sequence, formerly sung in some churches, and entitled Gaude flore virginali.

(Our Lady's full reply to St. Thomas:

The favorite devotion with which St. Thomas was accustomed to invoke his great Patroness, was the salutation of

Her Seven Joys, and we read how on one occasion Our Lady appeared to him, and after assuring him that his homage was most pleasing

to Her, inquired of him why he only commemorated Her Joys on earth, and not also those which formed Her crown in Heaven;

and he replying that he knew not which they were, She made known to him Her Seven Celestial Joys, after which time the Saint

constantly honored them, and composed the Sequence, formerly sung in some churches, and entitled Gaude flore virginali.

(Our Lady's full reply to St. Thomas: Say the Hail Mary seven times daily. First because the Most Holy Trinity honors Me above

all creatures; secondly because My Virginity has elevated Me above all the Angels and Saints; thirdly because the

great light of My glory illumines the heavens; fourthly because all the Blessed honor Me as Mother of God; fifthly because

My Son grants Me whatever I ask; sixthly for the grace bestowed on earth and the glory prepared in Heaven for My clients;

lastly on account of My accidental glory, which will go on increasing until the day of the general resurrection.

)

After the martyrdom of the Saint, when every memorial of his life and death was held dear at Canterbury,

the great stained glass window of the west transept of the cathedral was filled with a splendid representation of the

Seven Celestial Joys of Our Lady, together with the figures of the martyred prelate, and all the patron Saints of England.

The description of this window is left written by the hand that destroyed it – that namely of Richard Calmer – one of the

six Protestant preachers of the cathedral during the time of the Commonwealth. In his report of his proceedings,

he informs us that the commissioners fell to work on this great idolatrous window (to destroy it), whereon many

thousand pounds had been expended by outlandish papists. In that window were representations of the Holy Trinity,

and of the Twelve Apostles, and seven large pictures of the Virgin Mary, in several glorious appearances: such as of the angel

lifting Her into Heaven, and the sun, moon, and stars under Her feet; and every picture had under it an inscription beginning

with Gaude Maria (Rejoice O Mary), such as Gaude Maria, Sponsa Dei (Rejoice O Mary, Spouse of God).

And at the foot of that huge window was a title intimating that the window was dedicated to the Virgin Mary: In laudem et

honorem Beatissimae Virginis Mariae Matris Dei (In praise and honor of the Most Blessed Virgin Mary Mother of God).

It might be thought that the seven glorious appearances

had at least impressed the mind of this sacrilegious

fanatic with some feeling of admiration, yet he appears to have been chiefly possessed with a sense of satisfaction at having been

able to stand at the top of the city ladder, pike in hand, when no one else present would venture to the giddy height,

whence he was able to shatter the window to pieces – as he expresses it, rattle down proud Becket's glassy bones.

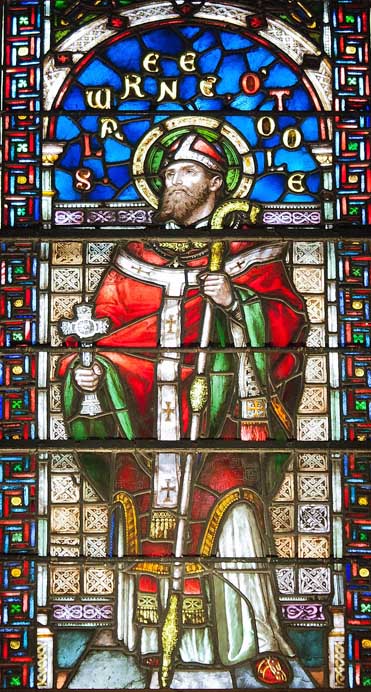

We will next pass on to the legends recorded in the lives of two Saints, contemporaries of St. Thomas, namely

St. Godric of Finchale and St. Laurence O'Toole of Dublin. The former of these, a simple uneducated peddler, after spending

many years in devout pilgrimages to the holy places of Jerusalem, Rome, and Compostela, retired to a wilderness near Durham,

where he lived a holy angelic life, the account of which has been written by those who were eye-witnesses of his sanctity.

On the walls of his hermit's cell hung a crucifix, and an image of the Blessed Virgin, which, as his biographer tells us,

were made the instruments of many marvelous favors. That poor hermitage was repeatedly visited by Angels and Saints,

as well as by the Queen of Angels, who on one occasion is said to have appeared to Godric in company with St. Mary Magdalene,

and, placing Her hand on his head, to have taught him the hymn, known as St. Godric's hymn.

The name of St. Laurence O'Toole is associated with two sanctuaries of Our Lady, one in Dublin,

and another in Wales, the history of which is related in the exceedingly beautiful and interesting life of the Saint preserved by Surius,

but without any particulars which would enable us to decide their precise locality. St. Laurence many times visited England,

and on one of these occasions returning from the court of Henry II, into his own country, he came to a certain seaport in Wales,

the name of which is not preserved, and was there detained by unfavorable winds. There was in the neighborhood a church which

had been recently built in honor of the Blessed Virgin, by a rich man of the country, but in consequence of the absence of the

bishop of the diocese, it had not yet been consecrated. A certain hermit or anchoret had constructed himself a cell attached

to this church, in which he abode that he might serve God more freely. To him the Blessed Virgin appeared in the night,

richly adorned and with a majestic countenance, and inquired of him why Her church had not yet been consecrated. And the anchoret

replying that it was because of the absence of the bishop, She made answer,

The name of St. Laurence O'Toole is associated with two sanctuaries of Our Lady, one in Dublin,

and another in Wales, the history of which is related in the exceedingly beautiful and interesting life of the Saint preserved by Surius,

but without any particulars which would enable us to decide their precise locality. St. Laurence many times visited England,

and on one of these occasions returning from the court of Henry II, into his own country, he came to a certain seaport in Wales,

the name of which is not preserved, and was there detained by unfavorable winds. There was in the neighborhood a church which

had been recently built in honor of the Blessed Virgin, by a rich man of the country, but in consequence of the absence of the

bishop of the diocese, it had not yet been consecrated. A certain hermit or anchoret had constructed himself a cell attached

to this church, in which he abode that he might serve God more freely. To him the Blessed Virgin appeared in the night,

richly adorned and with a majestic countenance, and inquired of him why Her church had not yet been consecrated. And the anchoret

replying that it was because of the absence of the bishop, She made answer, I will not have it consecrated by him,

but by Laurence of Dublin, for whose coming I have been waiting, that he, and none but he, might dedicate My church.

And this shall be a sign to him, for he shall not obtain a favorable wind until he has done my pleasure.

The hermit awoke, amazed with the vision; and as soon as it was day he sent for the lord of the adjoining castle who had founded the church, and declared to him what had taken place. The lord went at once to the Archbishop St. Laurence, and invited him to his castle, and receiving him honorably, made him a feast, and implored him to deign to consecrate the church. But the holy man replied that he could not do this in the diocese of another, and remained unmoved by all the prayers of his host. Then the latter related to him the vision of the anchoret, and all the words of the Blessed Virgin, till St. Laurence, convinced that it was indeed the will of God, and that the thing was not unlawful, but rather enjoined, the next day consecrated the church. And so soon as the Mass and other holy Rites were ended, and he had tasted bread, he entered into his ship, and with a favorable wind set sail for his own land. And from that time innumerable miracles were performed, and divine graces and favors poured out in this church.

On another occasion as he was about to set out for England and had already got on board the vessel, some of the

citizens of Dublin joined him, believing themselves sure of escaping the perils of the sea, if they sailed in his company.

However, they had not proceeded far before a great tempest arose, whereupon they all gathered round their holy pastor,

imploring him by his prayers to deliver them from the death that appeared to threaten them. But he encouraged them,

assuring them that if they followed his counsel, not one of them should perish. You know,

he said, that we are even

now building a church in Dublin, in honor of the Mother of God. Promise there to give to this work bountifully of the fruit

of those things which He has given to you, and I will promise you on the part of God, a tranquil sea and a safe voyage.

They at once made the required promise, offering their alms to the Archbishop with a good and ready will; for the ship was

loaded with their merchandise. Then the heavens cleared, the sea grew calm, and they reached land in safety praising God

and His holy servant.

But whilst speaking of the graces received from Our Blessed Lady by English Saints, it is impossible to pass over without notice one which stands out pre-eminent, both from its worldwide celebrity, and the lasting traces which it has left on the devotion of Catholics not in England alone, but throughout the whole of Catholic Christendom. I allude of course to the giving of the Carmelite Scapular to St. Simon Stock. The Order of Mount Carmel, whose glory it is to be called the Order of the Blessed Virgin, has some peculiar claims on the interest of English Catholics. England was the first European country which gave shelter to its religious, when driven by the persecution of the Saracens out of the Holy Land. It was to an Englishman, and on English soil, that the Ever Blessed Virgin gave the Scapular with Her own hands. In England the devotion of the Scapular took its origin and received its first extension, and in England also the first miraculous favor was granted to the use of that devotion.

It was in the reign of Henry III that two English knights, John Lord Vesey and Richard Lord Grey, having gone to the

Holy Wars, visited Mount Carmel in devout pilgrimage, and were thus surprised to find several of their countrymen leading an

eremitical life. Charmed with the sanctity of these hermits, they obtained leave to take back some of them to England,

among whom were Ralph Freburn, formerly a gentleman of Northumberland, and Ivo, or Alamon, a native of Brittany. The two noble

founders granted them lands in their own immediate neighborhood. Lord Grey gave the site for a convent at Aylesford in Kent,

on a spot close to the river Medway, where portions of the ancient buildings may still be seen. Lord Vesey planted his colony at Holn,

in the forest of Alnwick in Northumberland, and these were the first Carmelite houses erected in Europe. Ralph Freburn became

the first English Provincial, and gave the habit to Simon Stock, who up to that time had lived as a hermit in one of the Kentish woods.

Hardly had the friars been settled in England before they took measures for establishing themselves at the two Universities;

and St. Simon Stock was taking his degree at Oxford as Bachelor of Divinity at the very time that Humphrey Neckton, another Carmelite,

became the first professor of the Order at Cambridge. Simon's distinguished merit procured his election as General of the whole Order

at the first General Chapter, which was held at Aylesford in Kent in the year 1245. Four years later, in 1249, Michael Malsherb gave

the friars a certain habitation at Newenham, outside the town of Cambridge, where they continued forty-two years, afterwards moving

to a house which stood near the present site of Queen's College. But this removal did not take place until the year 1291,

and it must therefore have been at Newenham that the celebrated vision took place, which is assigned by the historians of the Order

to the date of 1251, and declared by them to have occurred in the oratory of the Carmelite convent at Cambridge. For it is said,

as St. Simon prayed in this oratory, the Blessed Virgin appeared to him holding the sacred Scapular in Her hand, and bestowed it

on him saying: Receive this Scapular, the sign of My Confraternity, a privilege to thee and thy Order; in which he that dieth

shall not suffer eternal fire; a sign of salvation, a safeguard in danger, the seal of an everlasting covenant.

We have already said more than once, that in detailing these traditions of a supernatural character, it is not intended

to pass any decision on their several claims to authenticity. But it must be remarked that this particular vision of St. Simon Stock

has been more formally approved as certain than most legends of a similar kind. We believe this vision to be true,

writes

Pope Benedict XIV, and that all ought to consider it as such. It is very precisely related by Swaynton, the companion and secretary

of the Blessed Simon, who declares that he heard it from his mouth: 'This, I, though unworthy, have written from the dictation of the

man of God.' The autograph was preserved in the archives of Bordeaux, and was brought to light when the controversy on those subjects

was taking place.

(Bened. XIV 'De Festis,' tom. ii. cap. 6. It is not surprising that the authenticity of this document

has been vilified in the modernist post-conciliar church, and the Feast of Our Lady of Mt. Carmel removed from the Calendar.)

In one old legend of St. Simon Stock it is added that Our Lady, when giving the Scapular to the Saint, declared that the land of

England was Her dowry, and that She held it under Her singular protection.

It is certain that St. Simon was himself the first to propagate the devotion of the Scapular in England, for he gave it not merely to religious persons but to laymen, among whom were the two kings, Edward I and his unfortunate son, Edward II. And it is worth our notice that the first miracle recorded as having taken place in connection with the Scapular was wrought in the person of a layman whom the Saint enrolled in the Confraternity. Having gone to visit the Bishop of Winchester on business connected with his Order, St. Simon had no sooner arrived in the city than the dean of St. Helen's parish church came to him beseeching him to come and assist a brother of his named Walter, who lay in a miserable state, dying as it seemed in despair of salvation, and obstinately refusing so much as to hear of sacred things. St. Simon hastened to the bedside of the poor man, whom he found bereft of reason, grinding his teeth, and with a hideous convulsed countenance. After recommending him to God in earnest prayer, he placed the Scapular around his neck, which was no sooner done, than the sick man returned to himself, and presently begging pardon of God with great contrition and many tears, received the Last Sacraments of Holy Church with the utmost devotion, and peacefully expired the same night. It is added that the dean, being still in great doubt of his brother's salvation, on account of the irregularity of his former life, the dead man appeared to him, and assured him that the graces he had received by the reception of that holy habit had enabled him to escape the snares of the enemy and had procured him the happiness of dying in the grace of God. Such is the story as we read in the life of St. Simon Stock, and it receives a certain confirmation from the fact that the name of Peter, a parish priest of St. Helen's, Winchester, appears as the founder of the Carmelite convent which was erected in that city in the year 1278.

England was not so happy as to give a place of sepulture to her saintly son, who in 1266 died at Bordeaux, where it

is believed his body still lies interred. But his Order always preserved a high place in the esteem of his countrymen, and the

Brown Scapular, so dear and familiar to ourselves, hung on the breast of many an English baron, such as Thomas, the martyred Earl

of Lancaster, as he was called, and Henry Earl of Northumberland. A story is related by Francis Potel in his book De Origine

et Antiquitate Ordinis Carmeli, which, as bearing on the subject of English miraculous images, I shall quote in this place.

There was a convent of Carmelites in the city of Chester, who according to the custom of the Order were wont to style themselves

Brothers of the Blessed Virgin Mary of Mount Carmel.

Some of the citizens took offence at the use of this title,

and spoke many injurious and contemptuous words about the friars, saying that they were rather worthy to be called brothers of

Mary of Egypt. But within a few days those who had so spoken were seized with divers sicknesses, many of them died,

and such evident signs of divine displeasure seemed to threaten the city, that the abbot of St. Werburgh's ordered a solemn

procession to be made, to appease the wrath of God. In this procession the Carmelites took part together with other religious Orders,

and as they passed a certain wooden image of the Blessed Virgin, which was held in great veneration in that city, many of them saluted it,

bowing their heads and repeating the Ave Maria. Then it was seen by all, that the holy image returned their salutations,

bowing its head also and extending its hand toward the Carmelites, and some even affirmed that they distinctly heard a voice

three times pronounce the words, Behold my brothers.

This event is said to have taken place in the year 1317,

in the reign of Edward II.

And here we may remark the singular favor shown to the Carmelite Order by that unfortunate monarch, who,

as has been before said, himself received the Scapular. When setting out for Scotland, to prosecute the war which terminated

with the battle of Bannockburn, he took with him a certain Carmelite friar named Robert Baston, who, when the king was in great

peril of being taken by the victorious Scots, promised him safety if he made some vow to Our Blessed Lady. Edward followed his

counsel and vowed, should he escape, to build a house of Her Order in England. In fulfillment of this vow he gave his manor house

at Oxford to the Carmelite friars, by a royal deed published by him at York, wherein he declares this grant to be made for the

devotion which we bear to the glorious Virgin Mary and for the fulfilling of a certain vow, which we made being in danger.

As mentioned above, the true origin of the Carmelite Order was sometimes doubted and disputed. This dispute continued

to cause a great deal of trouble (and even persecution) to the friars for many years, until the University of Cambridge,

which never forgot its early connection with the Order, appointed a commission of learned men, headed by their chancellor,

John Donewick, to examine into the claims of the Carmelites to antiquity. The result was that on February 23, 1374, they published

the following decree:

As mentioned above, the true origin of the Carmelite Order was sometimes doubted and disputed. This dispute continued

to cause a great deal of trouble (and even persecution) to the friars for many years, until the University of Cambridge,

which never forgot its early connection with the Order, appointed a commission of learned men, headed by their chancellor,

John Donewick, to examine into the claims of the Carmelites to antiquity. The result was that on February 23, 1374, they published

the following decree: We, having heard the various reasons and allegations, and moreover having seen, read, heard, and examined

the privileges, chronicles, and ancient writings of the said Order of the Blessed Virgin Mary of Mount Carmel, do pronounce, determine,

and declare (as is manifest to us by the said histories and other ancient writings), that the brothers of this Order are really the

imitators and successors of the holy prophets Elias and Eliseus.

(The persecution of the Carmelite Order culminated in the martyrdom of sixteen discalced Carmelite nuns, condemned to the guillotine by the French Revolution during the

Reign of Terrorin 1794. See image at right.)

Pursuing the traces to be found in English hagiology, indicating the existence of many sanctuaries, venerated as the

scenes of miraculous graces, we may quote a notice which occurs in the Chronologia Benedictino-Mariana, wherein mention is made

of a monk named Guntelin, who lived in England about the year 1299. In the early part of his life he had been renowned for strength

of body, but was also unhappily notorious for his vicious life. From this he was recalled, however, by a vision in which he beheld

the sufferings of the damned and the joys of the blessed; after which it seemed to him that he was conducted to a certain chapel

(the location of which we unfortunately do not know) where the Blessed Virgin appeared in great splendor, together with the holy

Patriarch St. Benedict. The latter having, according to monastic custom, said, Benedicite,

and Our Lady answering,

Dominus,

St. Benedict addressed Her in these words: Behold, O Lady, the novice whom Thou hast commanded me to bring hither.

And She addressing Guntelin, said, Art thou willing to live with Me and serve Me in My house?

He replied that he was.

Swear then on this altar,

She continued, that thou wilt ever serve Me, and keep the commandments of God.

And he took the required oath, whereupon the Blessed Virgin desired St. Benedict to reconduct him whence he came. From that time

Guntelin, entering the monastic state, entirely changed his life, and by his fidelity to his promise, deserved to be ranked among

the blessed.

Again we read of a certain Dominican friar of the convent of Our Lady in Derby, who was attacked with a sudden illness

whilst in the neighboring house of the Franciscans, and on his deathbed showed such extraordinary gestures of reverence as though

to some personage present of exalted dignity, that those who stood around him, inquired the cause. This house,

he replied,

is full of angels, and there are here present the glorious St. Edward our King, and Our Lady, whom let us salute.

The fathers,

hearing him speak thus, intoned the Salve Regina, which being ended, he smiled and said: Oh, how acceptable was your salutation

to the Queen of Heaven, for lo! as She listened to you, She smiled.

This anecdote is related both by Taegius and Gerard Frachetti,

historians of the Order of Preachers, and assigned by them to the year 1251.

Both Oxford and Cambridge had their famous images of Our Lady; that at Oxford being rendered memorable by the devotion of St. Edmund. It was before this image that when still a youth, he made his vow of perpetual chastity, and commending himself to the protection of the Blessed Virgin, chose Her for his spouse, and in pledge of his engagement placed on the finger of Her image a ring on which he had caused to be inscribed Ave Maria. He wore another similar ring on his own hand, and was buried with it. From the time of this solemn consecration of himself, as he confessed on his deathbed, he sought Her assistance in all his necessities, and never failed to find Her a refuge in trouble, and a deliverer in all temptations. The Lady chapel attached to St. Peter's church, was built by him for the use of himself and his pupils, and in it he was accustomed daily to recite the Canonical Hours, together with the Office of the Holy Ghost and the Blessed Virgin.

Concerning the image at Cambridge, a story is given in a manuscript preserved in the Vatican Library, of a certain young

student named William Vidius, who led an irregular kind of life, but nevertheless never laid aside his devotion to the Blessed Virgin,

and was accustomed daily to honor Her by reciting certain prayers before Her image. This youth had a certain comrade named James who

shared his room; and one night as they slept, James was awakened by the groans of his companion, whom he observed was trembling and

covered with sweat, as though suffering great terror. With some difficulty he succeeded in rousing him, and inquired what was the

matter. Well is it for me,

exclaimed Vidius, that I have been used to honor the image of the Blessed Virgin! But for

that I should have perished eternally. For this night I have stood before Christ the Judge Who required of me a strict account

of my life. The enemy was already about to seize my soul, when I beheld the Blessed Mother of God, and according to my custom,

invoking Her aid, She put the devil to flight, and by Her intercession obtained for me a further respite.

Perhaps the

image here alluded to may have been that venerated in the church of the Black Friars at Cambridge which stood on the spot

now occupied by Emmanuel College, concerning which John, the (Protestant) bishop of Rochester, wrote to Cromwell,

that there hath of a long time been an image of Our Lady in the said house of friars, the which hath had much pilgrimage

unto Her, and specially at Sturbridge fair; and for as much as that time draweth near, and also that the said prior cannot

well bear such idolatry as hath been used to the same, his humble request is that he may have commandment by your lordship

to take away the said image from the peoples' sight.

In investigating the scanty notices left us of these old English sanctuaries, what is preserved of their history

is obviously nothing in comparison with what has perished. There is scarcely a parish in England which has not some trace or

relic of the old devotion: in one place, we find Our Lady's well,

still preserved in the parish courtyard; in another,

as at Woodbridge in Suffolk, local tradition speaks of the famous image which formerly stood in the wall of the church, to which

much pilgrimage was made.

Indeed, if we may judge from the indications to be found in topographical histories, we should be

disposed to conclude that the English in Catholic times were distinguished in a very remarkable degree by their fondness for

this species of devotion (i.e. pilgrimage). The ancient form of the Bidding Prayer included a recommendation of all pilgrims –

Ye shall pray for all pilgrims and palmers, that Almighty God may give them grace to go safe and to come safe, and give us grace

to have part of their prayers, and they part of ours.

Many, perhaps most, of the localities thus visited were rendered venerable

by possessing the relics, and perhaps the incorrupt body, of one of our English Saints, such as that of St. Edmund at Bury,

St. Waltheof at Melrose, St. Etheldreda at Ely, or St. Editha at Wilton. In some the history of the pilgrimage is preserved,

whilst almost all records of the events which sanctified the locality, have passed from the mind of man. Thus the little parish

of St. Martha’s on the Hill, near Guildford in Surrey, takes its name from a hill still called Martyr's Hill. Whence it derived

this appellation is now unknown, but from a notice in the register of Waynflete, Bishop of Winchester, we learn that it was in

his time a place of pilgrimage, for we find him granting a forty days' indulgence to all who should resort to the parish church

on account of devotion, prayer, pilgrimage, or offering; and who should then say the Pater Noster, Ave Maria, and Credo,

and contribute an alms to the maintenance of the same.

The love of going on pilgrimage was so innate in the English people, that neither the

The love of going on pilgrimage was so innate in the English people, that neither the reformation

nor

the Great Rebellion sufficed to quench it, and Catholics were still found hardy enough to visit some of their favorite sanctuaries,

such as the tomb of St. Richard of Chichester, to which many were yearly in the habit of resorting on his Feast, long after the

Restoration. Memorials are found in many places of inns and wayside chapels, used by pilgrims, such as at Chapel House, and

Deddington in Oxfordshire, and on the former spot a skeleton was some years ago dug up, together with a silver crucifix and rosary.

How significant are such notices as those that occur in the pages of Leland, when he remarks how he passed in a wood by a chapel

of Our Lady, where was wont to be great pilgrimage,

or of the chapel of Our Lady of Grace, that standeth a little from the shore,

some time haunted by pilgrims;

or how there is still great pilgrimage to Our Lady

made in the village of Burgham.

What is there in modern times to attract the visitor in what Tanner calls the little barren island of Hilbury

(or Hilbre –

image at left) off the coast of Cheshire? Yet in ancient times faith and devotion beautified these barren rocks, for here the

monks of Chester had a cell, and frequent pilgrimages were made to Our Lady of Hilbyri.

London visitors to Margate and Ramsgate will doubtless remember the smaller watering-place of Broadstairs, lying between the two, where a few years ago might still be seen, near the pier, the remains of an ancient building, converted into a dwelling-house, but formerly the Chapel of Our Lady of Bradstow, where Her image was held in such veneration that ships as they sailed past the coast, were used to lower their top-sails to salute it.

Among the many parish churches dedicated to St. Mary,

how many are to be found associated with legends and traditions which

still keep a certain hold on the memory of the people. Thus at the village of St. Marychurch, near Torquay, a tradition survives

that the first Christian church built in that parish was begun, not on the hill now occupied by the parish church, but in a

valley lying to the west. Something however, it is said, always obstructed the progress of the work, and the builders found,

that as much of the walls as they raised during the day was sure to be pulled down by some unseen hand during the night.

At last a voice in the air is said to have been heard singing the words: If St. Mary's build ye will, ye must build it on the hill.

In consequence they were induced to begin their work over again, and build the church on the brow of the hill where it now stands.

Scotland, no less than England, was at one time rich in sanctuaries of Our Lady, among which were those of Scone, Dundee, Paisley, Jedburgh, and Melrose. The practice of devout pilgrimages was held in great esteem by the Scottish Catholics, and notwithstanding the savage character of the border warfare, English pilgrims to Melrose were never known to be molested. Riccardi in his history of Our Lady's Sanctuaries, quotes a treaty of peace between two Scottish clans, by the terms of which the rival chieftains bound themselves to make four pilgrimages to different Scottish shrines, for the repose of the souls of those of their enemies who had been slain by them in battle.

Hector Boëthius, in his history of Scotland, relates an incident which occurred at Haddington, during the time when the whole country was overrun by the victorious forces of Edward III. There was in that town a chapel of Our Lady, known as the White Chapel, in which a highly venerated image of the Blessed Virgin was preserved. An English soldier having entered the chapel for the purpose of plunder, seized this image with all its ornaments, and was in the act of carrying it off, when a large cross of very great weight which hung suspended from the roof, broke from its support and fell, crushing the sacrilegious robber to death, but injuring no one else within the building. He adds that the image had before this been regarded as miraculous, but that after this event the devotion of the people towards it greatly increased.

The history of another Scottish image, that of Aberdeen (image right), is yet more interesting from the fact that it was preserved

from sacrilege at the time of the

The history of another Scottish image, that of Aberdeen (image right), is yet more interesting from the fact that it was preserved

from sacrilege at the time of the reformation,

and is still an object of religious veneration. It was of wood, and

originally occupied the cathedral church of St. Macarius, whence, after having been venerated for nearly six hundred years,

it was moved in the early part of the sixteenth century by Gavin Dunbar, Bishop of Aberdeen. That pious prelate had succeeded

in erecting a bridge of seven arches over the river Don and, according to the custom of Catholic times, constructed a chapel on

the first arch of his bridge, in which he deposited the holy image. A little fountain sprang up close by, the waters of which

were believed to effect miraculous cures, and a certain heretic having endeavored to desecrate the fountain by casting filth

into its pure and limpid waters, was seized on the spot by a strange malady which caused him publicly to acknowledge that he

was struck by the hand of God. After this event, to preserve the holy image from any new profanation, it was carried back

to its former resting-place, and Gavin, whose palace adjoined the cathedral, passed no day without visiting it. It is said

that once while praying before the image, a voice came from it announcing to the good prelate the approach of evil times.

Gavin,

it said, thou art the last bishop of this city who will have the happiness of being saved.

This terrible

prediction is assigned to the year 1520, and the corruption of morals which in Scotland preceded the loss of the Faith seemed

to indicate a sad fulfillment of the words. Gavin himself enjoyed a high reputation for sanctity, and after the reformation

his body was disinterred by the heretics, and found whole and incorrupt, so that being struck with fear they did not dare to touch it.

The holy image was fortunate enough to escape the sacrilegious hands of the Scottish reformers.

It was first

of all saved from their fury by some pious Catholics, but afterwards came into the possession of the Protestants, who were always

withheld from destroying it, from the dread inspired by the judgments which seemed to fall on all who attempted to lay hands on it.

Thus, a band of furious zealots having once determined to make an end of this last relic of popery,

they were struck with

blindness, and although the image was quite exposed to view, they could not succeed in finding it. On the other hand the family

which gave it shelter received abundant benedictions; it seemed to bring a blessing with it, as the Ark of the Covenant had done

formerly to the household of Obededom, and at length so great an impression was made on the minds of this family, that, abjuring

their errors, they were reconciled to the Church, a crowning grace which they failed not to attribute to the intercession of Our Lady.

After a time William Laing, a Scottish Catholic, who is styled Procurator to the King of Spain, succeeded in obtaining possession of the image, which he deposited in a suitable place in his house, and we are assured that though the heretics often made their way thither, they never succeeded in beholding it. At last in 1623, Laing entrusted it to the captain of a Spanish ship, with orders to convey it to Flanders, and place it in the hands of the Infanta Isabella, then Governess of the Low Countries. (Isabella was daughter of King Philip II of Spain, and married, in 1598, Albert, son of the Emperor Maximilian II. Philip made over to them the sovereignty of the Low Countries – Holland and Flanders, and their government has been praised even by Protestant writers for its justice and clemency. After the death of her husband in 1621, Isabella entered the Third Order of St. Francis – see image below – and continued to rule alone until her death, which took place in 1633.)

After narrowly escaping the dangers of a frightful tempest, and engaging in a combat with some Dutch pirates, the ship cast anchor

off Dunkirk. The commandant of that port, hearing of the miraculous character attributed to the image, was at first disposed to

seize possession of it and send it to Spain; but he was turned from this purpose by a dangerous malady which suddenly attacked him,

and from which he continued to suffer until he placed the precious deposit in the hands of Father de los Rios, an Augustinian monk

in the suit of the Infanta, who happened then to be at Dunkirk. (This is the same Fr. de los Rios who wrote the book

After narrowly escaping the dangers of a frightful tempest, and engaging in a combat with some Dutch pirates, the ship cast anchor

off Dunkirk. The commandant of that port, hearing of the miraculous character attributed to the image, was at first disposed to

seize possession of it and send it to Spain; but he was turned from this purpose by a dangerous malady which suddenly attacked him,

and from which he continued to suffer until he placed the precious deposit in the hands of Father de los Rios, an Augustinian monk

in the suit of the Infanta, who happened then to be at Dunkirk. (This is the same Fr. de los Rios who wrote the book

Hierarchia Mariana,

promoting the devotion of total consecration to Jesus through Mary.) The Archduchess gave orders

for the image to be at once moved to the chapel attached to her palace at Brussels, and charged William Laing to collect all

the documents relating to its previous history, and the miracles connected with it.

In 1626 Fr. de los Rios petitioned the Archduchess to allow the image to be transferred to the newly-built church of the Augustinian Fathers, and its translation to this new resting place was effected on May 3 of the same year with the utmost pomp. All the clergy, nobility, and magistracy of the city were present, and Pope Urban VIII granted a plenary indulgence to all who should assist at this ceremony. The procession set out from the palace amid the ringing of bells and the thunder of artillery, and could scarcely make its way though the vast throng of assembled spectators. The pupils of the college, directed by the Augustinian Fathers, rode on horseback at the head of the procession, carrying richly ornamented banners; then followed the various confraternities, Religious Orders, and collegiate bodies; and the holy image at last appeared, decked for the occasion with the Infanta's jewels, and covered with a robe glittering with gold and precious stones. The Infanta herself followed on foot surrounded by the chief officers of her court, and on reaching the Augustinian church, Mass was celebrated for the good success of Her Highness, and the image was solemnly deposited in the chapel prepared for it.

The festival lasted altogether ten days, during which several remarkable graces and miraculous cures were obtained, some of which are narrated very circumstantially by the historians of this sanctuary. A Confraternity of Notre Dame de Bon Succès (Our Lady of Good Success, as the image was then called) was formed, the Infanta herself being the first to be enrolled in it; whilst Marie de Médicis, the consort of Henri IV, inscribed her own name, kneeling as she did so before the sacred image.

When the revolutionary troubles of the 18th century broke out in Brussels, the Augustinians were stripped of their goods and obliged to leave their convent. But Our Lady of Aberdeen was once more saved from desecration, and singularly enough was again committed to the guardianship of British hands. An English Catholic gentleman of the name of Morris kept the image in safe custody until the year 1805, when by a decree of the Emperor Napoleon, the church of the Augustinians was annexed to the parish of Finistére, and the Catholic worship having been restored, the image was installed in its former resting place. Here however it did not long remain, for in 1814 the Protestants having obtained a grant of this church, Our Lady's image was removed to the parish church of Finistére and placed in a niche by the side of St. Joseph's altar. In 1852, M. Van Genechten, curé of the parish, caused a chapel to be erected to receive it, and on May 12, 1854, the Confraternity of Notre Dame de Bon Succès was restored by the authority of the Archbishop of Malines, with Her Royal Highness the Duchess of Brabant accepting the office of honorary provost.

We have called this history unique, because in point of fact no other instance is on record of any of our ancient images having been preserved down to our own time as objects of popular devotion. (As mentioned in Issue No. 201, Fr. Northcote seems to have been ignorant of Our Lady of Ipswich, widely believed to be preserved in Nettuno, Italy.) History however tells us of one holy image which was rescued after falling into the hands of the heretics; its restitution forming one of the articles of peace extorted by a French King from the sacrilegious ministers of Edward VI.

The story is too remarkable to be omitted here. The celebrated image of Our Lady of Boulogne was believed to have

been miraculously brought to that town in the 7th century (image of replica at right). Early in the 8th century,

it was visited by devout pilgrims from all lands,

among whom we find the name of St. Lugal, an Irish Archbishop. Godfrey of Boulogne (leader of the First Crusade and the first ruler

of Jerusalem after its conquest) made an offering to this holy image, of the royal crown of Jerusalem, which he himself would never

wear (he preferred the title

The story is too remarkable to be omitted here. The celebrated image of Our Lady of Boulogne was believed to have

been miraculously brought to that town in the 7th century (image of replica at right). Early in the 8th century,

it was visited by devout pilgrims from all lands,

among whom we find the name of St. Lugal, an Irish Archbishop. Godfrey of Boulogne (leader of the First Crusade and the first ruler

of Jerusalem after its conquest) made an offering to this holy image, of the royal crown of Jerusalem, which he himself would never

wear (he preferred the title Advocate of the Holy Sepulcher

), and even his mother Ida built the church in which this

treasure of the Boulognese continued to be venerated up to the calamitous days of 1793.

Our Lady of Boulogne was always an object of special devotion on the part of the (Norman) English. Many of their

kings came hither in person, and in 1264 the English bishops held a council here at which St. Louis and the Papal Legate assisted,

with the view of mediating between Henry III and his barons. Here too in 1308 was celebrated with extraordinary pomp the marriage,

doomed to so unhappy an issue, between Edward II of England and Isabella, the she-wolf of France;

on which occasion very rich

offerings were made to Our Lady's shrine; and when a few years later the queen led a hostile force against her unhappy husband,

and deprived him of his crown and his life, the French knights who had joined her standard and who believed themselves only fighting

in defense of her just rights, on their return to their own country made a pilgrimage of thanksgiving to Our Lady of Boulogne.

King John of France believed his deliverance from his long captivity in England to have been obtained in consequence of a vow made by him to visit this shrine in pilgrimage, and on landing at Calais he walked from thence to Boulogne to accomplish his devotions; and during the reign of Henry V, when the English held possession of the country we find the brave earls Talbot of Shrewsbury and Beauchamp of Warwick making magnificent offerings – Talbot presenting a robe of cloth of gold adorned with massive golden lion's heads, whilst Warwick offered a golden statue of the Blessed Virgin with the dragon under Her feet.

An English merchant also enriched the treasury with a turquoise of such extraordinary value that it was placed in the cross known as the Great Cross, and was considered its greatest ornament. The enormous riches of this sanctuary were further increased in 1514 by the offering of an English princess of the Tudor lineage. Mary, sister to Henry VIII, being affianced to Louis XII of France, landed at Boulogne, on her way to her husband's court, and immediately proceeded to the sanctuary, where she left an arm of massive silver, enameled with the armorial escutcheons of France and England. Indeed the Boulogne treasury seems to have rivaled that of Loreto in wealth. It possessed more than a hundred golden reliquaries, eighteen great silver statues, and a prodigious quantity of diamonds, rubies, and sapphires, to say nothing of the silver hearts, arms, legs and other votive offerings – the French sovereigns paying every year the tribute of a golden heart to Our Lady as to their feudal sovereign.

All these riches fell into the hands of Henry VIII and his brutal soldiery. In his younger years Henry had visited the church as a pilgrim and knelt before Our Lady's shrine in company with his gallant rival Francis I. But in 1544, war having broken out between the two countries, the English laid siege to Boulogne which was betrayed into their hands by some Italian mercenaries, and the town being taken, was given up to pillage. The soldiers hastened to the cathedral, and having made themselves masters of the riches which had accumulated there during nine centuries, they seized the sacred image itself and carried it back with them to England as a trophy of war. The chapel of Our Lady was entirely destroyed, and the church itself converted into an arsenal. The town remained in the hands of the English for five and a half years, during which time the garrison was continually swept away by pestilence, and had to be constantly recruited, until at length no soldiers could be found willing to accept the service, and they had to be sent over from England in chains.

In 1550 Boulogne was restored to France, and Henri II, after making his solemn entry into the town, accomplished a vow which he had made two years previously by offering a new image of solid silver to replace the old miraculous statue which had been carried to England. Magnificent as the new image was, it did not console the people of Boulogne for the loss of the old one, and the King therefore caused an article to be inserted in the treaty of peace concluded between him and the government of Edward VI, according to which the latter prince was required to give back Our Lady of Boulogne as the Philistines in old times had been compelled to restore the Ark of Israel. The English ministers were not at that time in a position to refuse any demands made on them, and the treaty, a most humiliating one to the national pride, was reluctantly agreed to. The image of Our Lady was sent back to France, together with all the ordnance stores captured at the taking of the town, and the clergy of Boulogne going forth in procession conducted their treasure back to the cathedral, where it soon drew to its feet new crowds of pilgrims.

Early 20th Century Procession of Our Lady of Boulogne.

Henrietta Maria, the unfortunate Queen of Charles I, was the last of our English sovereigns whose name appears on the list of those who made their offerings to this venerable image. It escaped the desecration of the Calvinists, and was at first even spared the revolutionary hordes in 1791, when they destroyed every other relic of religion in the city. But this act having drawn on them the accusation of moderation, they proceeded to vindicate themselves of the odious charge by publicly burning the sacred image, and putting up the cathedral to be sold by auction. It was purchased with Our Lady's chapel by some speculators, who caused the venerable edifice to be pulled down and utterly demolished, and thus, as it was hoped, every memorial of the old devotion was swept away. In 1820, however, an enterprising priest, the Abbé Haffreingue, succeeded in purchasing the site of the old cathedral and devoted himself to the task of its restoration. Persevering in his design for forty years in spite of a thousand difficulties; he lived to see his noble efforts amply rewarded; for not only have we in our days witnessed the consecration of the new cathedral, but we have beheld the ancient pilgrimage revived, and Our Lady of Boulogne yearly attracting to Her altar (with a replica of the original image) crowds of devotees.

NEW: Alphabetical Index

Contact us: smr@salvemariaregina.info

Visit also: www.marienfried.com